Robert Maranto served in the U.S. government during President Bill Clinton’s administration and on his local school board and is the 21st Century Chair in Leadership in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas; [email protected].

Martha Bradley-Dorsey is a private researcher affiliated with the University of Arkansas with both state legislative research and academic experience; [email protected]. Maranto and Bradley-Dorsey last appeared together in AQ with their article “Can Academia and the Media Handle the Truth?” in the fall 2020 issue.

Introduction

In most societies, through most of human history, free speech was abnormal, even abhorrent. As psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues, this likely reflects our evolution as a species, in which small bands competed with others for resources, making group loyalty, solidarity, and deference to authority evolutionarily advantageous in external conflicts.1

Modernity has done much to change this, particularly in the West. From John Stuart Mill in 1859 to his contemporary defender, Danish journalist Jacob Mchangama, most intellectuals have backed an open, noncoercive marketplace of ideas as the best means of divining truth, and generally lauded technological innovations from the printing press to the Internet which enabled the exchange of ideas. Indeed, as Mchangama details, in many respects the arguments for and against free speech have changed little since the Greeks, involving tradeoffs between the relative values of feeling free to seek knowledge or just express one’s thoughts, as opposed to protecting against giving offense or eroding public morals.

As the recent assassination attempt against Salmon Rushdie reminds us, the Islamic Republic of Iran, like the Medieval Vatican, finds free speech unacceptable since the regime claims to know the truth and thus has no reason to tolerate error, which could only cause individual and social harm.2 In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Marxist regimes took exactly the same approach regarding the infallibility of the Communist party, leading apostates to publish works like the essays in Richard Crossman’s brilliant, and now largely forgotten The God That Failed.3

In the U.S., as Keith Whittington details, before 1900 U.S. higher education existed largely to train ministers and connect elites—neither free inquiry nor free speech were essential values. Professors had no tenure. Controversial speakers like temperance crusader Carrie Nation faced student rioters at UC/Berkeley not unlike those attacking Milo Yiannopolous at the same school a century later.4 Free speech and free inquiry only became important higher education values in the twentieth century as campus missions shifted from supporting orthodoxy to producing and disseminating knowledge, missions requiring conjecture, freely proposing and testing sometimes controversial ideas. The new missions fostered the development of tenure, so professors could even write tomes that might offend financial benefactors. But, as free inquiry defenders such as Whittington and the recently deceased James R. Flynn have lamented, the new missions sometimes faced (usually external) attacks, especially during the McCarthy era.5

In the twenty-first century, free speech and its twin, free inquiry have increasingly come under fire, and to a far greater degree than in the 1950s, censors come from within academia. Various forms of critical theory have gained substantial influence in U.S. higher education, where adherents use their power to brand free speech and free inquiry as reinforcing the power of the privileged and endangering women and people of color. This is ironic given that as sensible liberals like Mchangama this year and Jonathan Zimmerman6 last year detail, by definition, the real powerless lack money and bureaucratic backing: free speech is the only tool they have. Every significant civil rights movement in U.S. history, including a few on the right like the homeschool movement and the pro-life movement, gained influence through free speech.

Another threat to free speech comes from contemporary elite child-raising cultures which emphasize avoiding harm, including offensive speech, thus narrowing young people’s views of permissible speech. This value system enables social media activists to quickly punish dissenters. These activists often get training and support from university “safety” bureaucrats, as Greg Lukianoff and the omnipresent Jonathan Haidt show.7 College and university presidents from the University of Central Florida to Princeton use such bureaucracies to tar critics as bigots and then terminate them to warn others, eviscerating dissent.8 Eric Kaufmann provides survey evidence indicating that nearly a tenth of left leaning professors and about a third of conservatives have faced sanctions for their views.9 No systematic empirical analyses examine whether students face similar challenges, though the 2021 survey discussed below shows that 80 percent of college students in the U.S. censor their own views.10

Here, we use data from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE, since renamed the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression to reflect increasing problems off campus) on institution speech codes, and surveys of undergraduates regarding support for free speech and perceptions of free speech climates on 154 campuses. The FIRE studies seem methodologically sound, coming from a data team led by a well-published and well-credentialed social psychologist. Amazingly, scholars and journalists have failed to tap into this rich, publicly available data, demonstrating a remarkable lack of interest in the topic, or perhaps fear of what they might find. Here, we divide the sample into the twenty most and twenty least receptive campuses for free speech (high and low FIRE), in effect using a most similar systems design often employed in comparative politics, selecting cases based on the key dependent variable, free speech in this case, in an inductive analysis. Despite the small number of cases, we find interesting results, which beg for large scale inquiry.

In our analysis public institutions and those outside the Northeast have higher free speech. High prestige campuses have lower free speech. The background of institution leaders seems related to free speech, though it is unclear whether leaders shape the free speech climate or pro-free speech institutions pick different types of leaders (or both). Notably, leaders who have spent their entire careers in academia preside over institutions with less supportive climates for free speech, indicating that intellectual freedom is no longer a core academic value. Instead, it is leaders with substantial experience outside the ivory tower who lead schools which best protect free speech.

The Data

Here, we offer an empirical study using 2021 student level data from 154 campuses provided by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education.11 FIRE graded campus speech codes authored and implemented by university administrations, giving higher scores to those prioritizing free expression. In addition, from February 15 to May 30, 2021, FIRE surveyed seventy-four to 271 full time undergraduates per campus (n=37,092), sampling larger numbers at larger campuses. FIRE used a twenty-eight-item survey measuring various opinion items as well as support for free expression on campus (including for allowing liberal and conservative speakers), relative comfort with discussing or hearing discussions about controversial subjects, and perceptions of the general climate regarding free expression on campus.12 FIRE combined these items into an index of free speech, a continuous variable with a mean of 59.76, and a standard deviation of 1.42. On SPEECH, the highest ranked, or most pro-free speech institution in the 2021 dataset is Claremont McKenna College (72.27) while the most restricted speech environment was at DePauw University (50.80). Indicating relative stability, in the 2022 rankings Claremont McKenna College (CMC) fell to sixth of 203,13 with the University of Chicago taking the top spot, while DePauw remained low, at 178th (FIRE, 2022). The full 2021 list of top and bottom twenty schools is below.

For this study, we compare the twenty highest and twenty lowest college finishers in terms of the preservation of Mill’s marketplace of ideas, on a range of variables. We use simple crosstabulations for nonquantitative data such as region, public-private status, and the characteristics of institution presidents, along with occasional use of comparisons of means for quantitative variables like size of undergraduate enrollment, and state level party politics (Biden vote percentage in the state).

Findings

Sector, Size, and Vote. Sixteen of the twenty lowest free speech institutions are private sector institutions, while sixteen of the twenty highest free speech institutions are public sector. In short, among the highest and lowest finishers, public and private sector institutions are perfect opposites. Further, 2021 was no anomaly. In the just published 2022 FIRE rankings, nineteen of the twenty lowest free speech institutions are private sector while eighteen of the twenty highest free speech institutions are public sector. As we argue elsewhere, this may reflect the ability of private sector institutions to define narrow, and often sectarian missions, and to value community more than truth-seeking.14 Notably, in the 2021 rankings none of the twenty highest free speech schools but three of the twenty lowest free speech schools were Catholic (Boston College, Fordham University, and Marquette University), with the first two led by Jesuits, a matter we will explore in future analyses. Moreover, the 2021 high free speech twenty includes just one liberal arts college (Claremont McKenna), compared to four liberal arts colleges on the low free speech list, all in the Northeast (Middlebury, Colby, Bates, and Connecticut).

Likely reflecting public-private sector differences, higher free speech institutions have larger enrollments, a mean of 22,548 full time undergraduates compared to just 12,608 at low free speech institutions. We also looked at the voting behavior of the states where campuses are located, since as noted, at least in higher education, threats to free speech and free inquiry now come mainly from the left. Here, we find no notable differences. High free speech institutions are in states with a mean 51 percent 2020 Biden vote, compared to 53.1 percent in states where low free speech institutions are located.

Region and Prestige

Geographically, eleven of the lowest twenty free speech schools but just two of the twenty highest free speech schools are in the Northeast, the region of so many prestige institutions. No Ivy League school makes the list of twenty top free-speech schools, though Princeton makes the bottom twenty. In contrast, just four of the low free speech schools but nine of the high free speech schools are in the South; likewise, three of the bottom twenty but six of the top twenty are in the West, while the Midwest has two bottom twenty schools and three in the top twenty. These findings fit survey research by Samuel J. Abrams indicating greater ideological diversity among faculty outside the Northeast.15

We suspect that, as Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt argue, greater ideological diversity facilitates free speech since more faculty and students will encounter and become familiar with people with dissenting views.16 Lukianoff and Haidt also argue that institutions serving more privileged student bodies allow less free speech since dissent now offends elites. Empirically, one Brookings Institution paper from 2017 found that higher tuition institutions had more restrictive speech policies.17

Here, we measure prestige by the undergraduate acceptance rate for spring 2020, a measure with high face validity. Distinguishing institutions with acceptance rates above and below 40 percent, we designated the latter as high prestige. Only 30 percent (six of twenty) of high free speech institutions are high prestige, with two of these (the University of Florida and Florida State University) having acceptance rates only slightly below 40 percent. In contrast, among the lowest twenty free speech schools, 55 percent (eleven of twenty) are high prestige institutions.

In short, we find concerning evidence that those campuses closest to the centers of power, and more involved in educating (or perhaps we should say training) elites are less supportive of free speech. It may be that as the Vietnamese say regarding corruption, the roof protecting free expression in higher education leaks from the top.

Campus Leadership and Free Speech

Terminal Degrees of Institution President

Background of Institution President

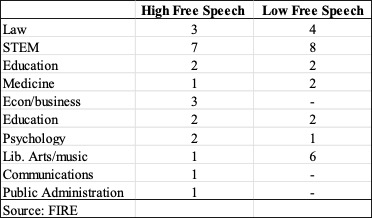

The table above presents the terminal degrees and backgrounds of institution presidents, as coded from individual and institutional wiki sites. Presidents with multiple terminal degrees (n=8) are counted more than once. We code presidents serving in fall 2020, shortly before the FIRE survey, unless they are newly appointed, in which case we coded the president serving in fall 2019. Again, even where relationships exist in the small sample, they cannot be considered causal in part since boards—whether supportive, indifferent, or hostile to free speech—likely select presidents who fit those values. An interesting case in point is Mark Kennedy, a former moderate Minnesota Republican congressman who led the University of North Dakota successfully, and then took the helm in 2019 at the high free speech University of Colorado, only to resign in 2021 shortly after Democrats gained a majority on the Board of Regents for the first time in forty years. Kennedy now leads a bipartisan think tank. A similar example is Nebraska Republican Senator Ben Sasse, a college president before becoming a senator who had earned a history Ph.D. from Yale. Sasse is at this writing resigning his senate seat to become President of the (high FIRE) University of Florida—a matter of some controversy in Gainesville. It seems most unlikely that a low FIRE university would offer Sasse its presidency.

Even in the small sample, some differences seem notable. The two presidents with doctorates in economics and agricultural economics, and a third whose terminal degree is an MBA (Kennedy), all led high-free speech institutions. On the other hand, six of the seven presidents with doctorates in liberal arts or music led low free speech institutions, a finding not surprising given the influence critical theory now holds in these fields. Interestingly, five of the low free speech institutions but only one of the high free speech institutions are led by women. This might reflect disciplinary differences: three of six female leaders have music or liberal arts terminal degrees, and a fourth, a lawyer running Bates College, has a B.A. in history. More controversial explanations exist. Psychologists Cory Clark and Bo Winegard offer an evolutionary explanation of gender differences among academics in their relative support for free speech versus community when those values exist in tension.18 In contrast, some evidence suggests that women may occupy more tenuous positions in organizations traditionally run by men, and thus may lack the power to change popular (censorious) policies.19 Assuming these findings hold up in large n quantitative research, these are matters which should be discussed rather than dismissed out of hand.

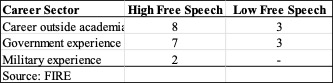

Given the relative insulation of the ivory tower from political and business networks and the possible broadening impacts of experience across sectors, one might expect campus presidents with external political or bureaucratic experience to be more supportive of free speech, and pluralism generally, as seems true of public executives.20 This may, unfortunately, suggest that free speech is now more valued in society than in the academy. Even this small data set offers support for this hypothesis. Among the twenty high free speech institutions, eight presidents had substantial experience outside academia, compared to three of those leading low free speech institutions. Seven presidents (Purdue, Colorado, Florida State, Arizona State, Kansas State, Mississippi State, and Auburn) had at least three years of political or government experience, compared to just three from the twenty low free speech institutions (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Miami, and Bates). The only two presidents with identifiable military experience led high free speech institutions: Florida State and Kansas State, with KSU led by an alumnus, a retired Air Force general.

Summary and Next Steps: Is There a Free Speech Future in the Ivory Tower?

With the caveat that this is preliminary and small n research, we suggest several findings sufficiently robust that they are likely to hold up. First, region matters, with the highly influential Northeast notably less supportive of free speech than other regions. Second, sector matters. Public institutions seem more supportive of free speech and free inquiry, particularly when compared to private liberal arts colleges and Catholic institutions, which might instead prioritize other values like community or “safety,” broadly defined. Notably, public institutions need support from state legislatures, which are not always politically correct. Third, prestige matters, with the most prestigious sections of higher education having the climates least supportive of free speech. To the degree that these institutions train future elites, this has disturbing implications for the future of free speech in America.

These regional and institutional settings are structural, far more difficult to alter than shorter-term factors like leadership, which may either influence or be influenced by the free speech climate of an institution, with campuses more supportive of free speech perhaps selecting different sorts of leaders. Higher education leaders with experience outside academia, leaders with business or economics degrees, and leaders without backgrounds in liberal arts and music may be more likely to facilitate a marketplace of ideas. The first finding is particularly concerning: leaders who have spent their entire careers in higher education seem less supportive of free speech, suggesting that free speech is now less valued inside the academy than elsewhere. In other words, we have reasons to fear that as regards free speech, higher education cannot save itself. Institutions may need dramatic external interventions, perhaps in the form of U.S. Department of Education policies barring public funding of institutions which show contempt for student and faculty First Amendment rights. Encouraged by state policymakers, boards must remove campus leaders who trample on such rights. Otherwise, free speech and free inquiry will cease to be important aspects of U.S. higher education in the twenty-first century.21 This would have horrendous implications for our democracy. We need congressional hearings on this.

1 The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (New York: Knopf, 2012).

2 Jacob Mchangama, Free Speech: A History from Socrates to Social Media (New York: Basic Books, 2022).

3 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949).

4 Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

5Flynn’s last work, A Book Too Risky to Publish, discussed this at length. See Maranto’s AQ review “Suppressing Speech: Worse than McCarthyism,” from spring 2022.

6 Free Speech and Why You Should Give a Damn (Buffalo: City of Light Publishing, 2021).

7 The Coddling of the American Mind (New York: Penguin Press, 2018).

8 Robert Maranto, Catherine Salmon, Lee Jussim. (2022). “Cut Their Pay and Make Then Teach,” RealClearEducation,” June 9, 2022.

9 Eric Kaufmann, “Academic Freedom in Crisis: Punishment, Political Discrimination, and Self-Censorship,” CSPI, March 1, 2021.

10 College Free Speech Rankings: What’s the Climate for Free Speech on America’s College Campuses, 2021, FIRE, RealClearEducation, and College Pulse, https://reports.collegepulse.com/hubfs/2021_SpeechRankings_Report.pdf.

11 Foundation For Individual Rights in Education. (2021). “2021 College Free Speech Rankings,” at https://www.thefire.org/research/publications/student-surveys/2021-college-free-speech-rankings/. The 2021 study included 159 campuses, but ranked 154, excluding five campuses with religious or other missions explicitly superseding free speech (Hillsdale, BYU, Pepperdine, St. Louis, and Baylor). FIRE has since issued the 2022 report, with a somewhat larger sample.

12 Demographic variables were collected separately. The survey used a two-stage validation process to ensure students were enrolled and applied a post-stratification adjustment based on demographic distributions from multiple data sources.

13 Some informants believe this fall from first to sixth reflected a single widely publicized incident, the now ongoing disciplining of CMC Government Professor Christopher Nadon.

14 “Yelling FIRE on Campus? Testing Undergraduate Free Expression in Higher Education,” presented at the annual American Political Science Association meeting in Montreal, September 15, 2022.

15 “There are conservative professors. Just not in these states,” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/03/opinion/sunday/there-are-conservative-professors-just-not-in-these-states.html.

16 The Coddling of the American Mind, op. cit.

17 Richard V. Reeves, Dimitrios Halikias, “Illiberal Arts Colleges: Pay More, Get Less (Free Speech),” Brookings Institution, March 14, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/illiberal-arts-colleges-pay-more-get-less-free-speech/.

18 Sex and the Academy. Quillette, October 8, 2022.

19 Robert Maranto, Kristen Carroll, Albert Cheng, Manuel P. Teodoro, “Boys Will Be Superintendents: School Leadership as a Gendered Profession,” Phi Delta Kappan 100, no. 2 (2018).

20 Robert Maranto, Beyond a Government of Strangers (Lanham, Md: Lexington Press, 2005).