Thomas L. Jeffers is emeritus professor of literature at Marquette University; [email protected]. Professor Jeffers is the author of Norman Podhoretz: A Biography (2010), Apprenticeships: The Bildungsroman from Goethe to Santayana (2005), and has written widely on nineteenth and twentieth century literature. He last appeared in AQ in the fall of 2020 with “Countering the Counterculture: ‘A Little Management.’”

When around 1954 Midge Decter decided to divorce her husband Moshe (the anti-Stalinist she’d married in 1948), leave the placid Queens suburb of Glen Oaks, and move back to a “leafy” street in Greenwich Village, where their marriage had begun, a friend asked, “Doesn’t anyone want to lead the life of quiet desperation anymore?” At age twenty-three and twenty-four, Midge had borne two girls, and, as she wrote in her memoir, An Old Wife’s Tale (2001), “to the naked eye there seem[ed] to be no drastic difficulty.” Quietly desperate, however, she did feel: speaking of herself in third person, she “‘looked into the mirror one morning’ and for the first time feeling truly young—in the sense that she saw years and years of life stretching before her—asked herself in horror, ‘Is this all there is going to be forever?’” Not that Moshe was to blame, as she always acknowledged (she kept his name because she’d begun to publish under it, a mistake, she later thought). But she never ceased regarding the divorce and the remove to have “saved my own life.”

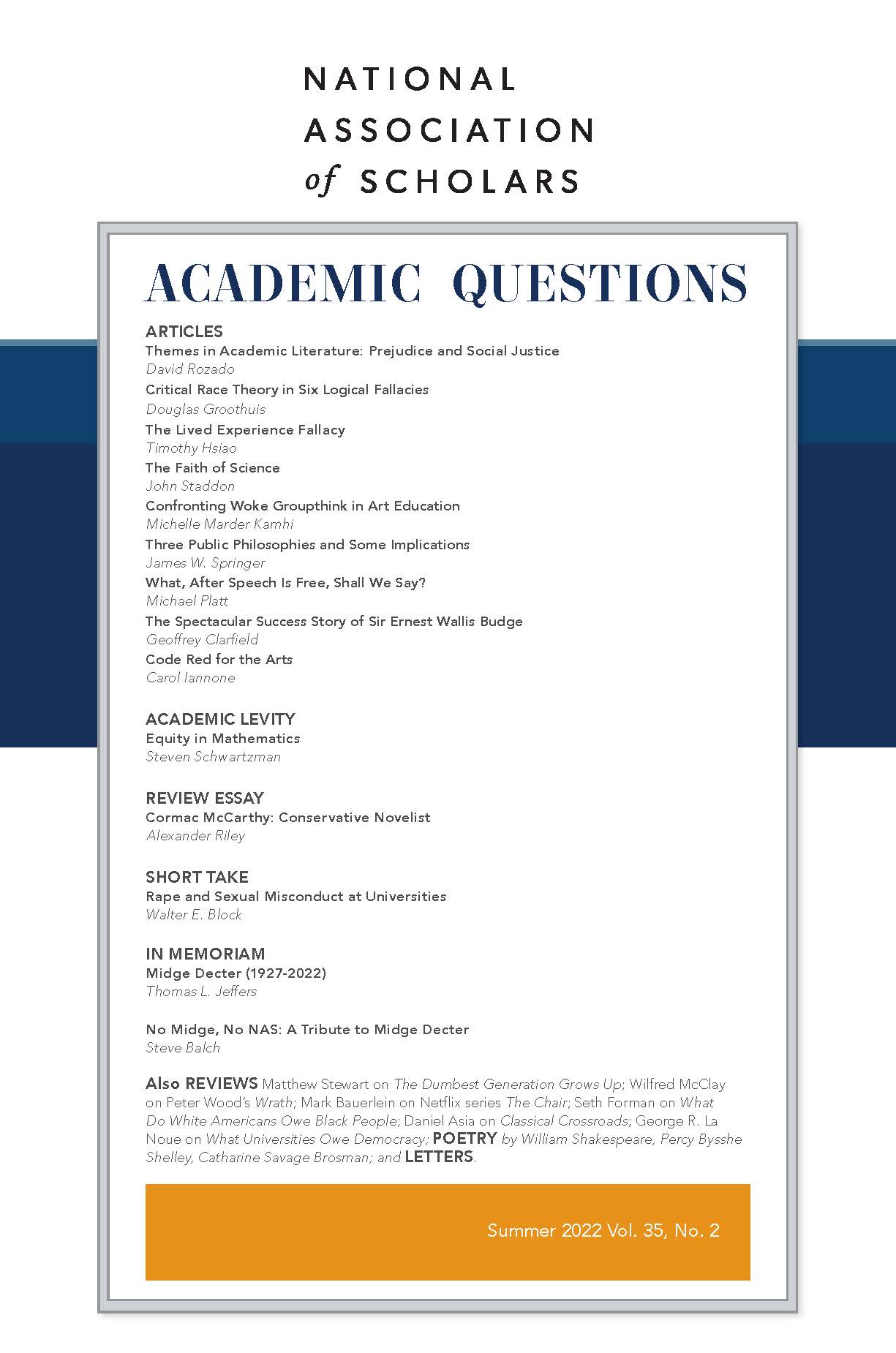

Midge’s life—she died at ninety-four on May 9—was for many readers coupled with that of Norman Podhoretz, the writer and editor who became her second husband in 1956. But as an intellectual force she was formidably independent. In addition to her memoir, which I quote throughout this piece, she published four books—The Liberated Woman (1971), The New Chastity (1972), Liberal Parents, Radical Children (1975), and Rumsfeld (2003)—all lucidly argued, spot-on in discrimination, and, in the 1970s trilogy especially, rich in anecdote about the way Americans lived in the wake of the 1960s’ derangement of relations between the sexes and the generations. Those books, long out of print, should be reprinted.

Always down-to-earth, Midge, whom I interviewed for many hours when researching a biography of Podhoretz, was a lively raconteur. I wasn’t the first to hear her say that if she brought him coffee, he brought her courage; or that, whatever his powers of thinking and writing, what she liked most was that “he amuses me.” Which—bringing courage and amusement—is what she did for audiences interested in the “culture wars” of the past half-century. Joseph Epstein once told me of a “family values” conference at which Midge, the keynote speaker, sighingly protested that she preferred not to say anything. Her own family was a shambles: four children, all of whom had gone through divorces, and the older of her eventually thirteen grandchildren often seeming adrift. But then, noticing who was attacking “the family” as an institution, she realized she had to stand up for its “values.” What was amiss with families could never be set right without grasping the societal norms that were as old as the race.

Born in 1927, the third of three daughters to the Rosenthals, a Jewish family in St. Paul, Marjori (but always called Midge) relished, from the start, what the poet William Blake called “Mental Fight.” One leftist clique later dubbed her “the Dragon Lady,” and she plainly didn’t mind being the designated conservative on panels where, before “deplatforming” had been heard of, at least some diversity of views was expected. “Could there be any greater happiness than that?” After all, she said, “the smugness of my opponents tended to weaken their capacity to argue their case,” and standing alone usually meant getting a measure of sympathy from the audience.

They pasted the neoconservative label on her, but today we need to know something of who the neocons were and how they got there. They distinguished themselves from “paleoconservatives” but in practical terms were united with them. Having grown up during the Depression and “Oh what a lovely war,” waged to rid the world of its most lethal antisemites, neocons like Irving Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Podhoretz had been “liberals”—specifically of the anti-communist variety. From Harry Truman to Lyndon Johnson, they heartily endorsed the foreign policy consensus that America had a moral obligation to defend capitalist democracy, containing and even pushing back the expansive dictators of the Soviet Union, China, and their surrogates. What differentiated paleo and neo, though, was, as Midge explained, that “we had known the leftists”—the soft-on-communism herd—“very intimately: we had been reading their books and magazines for years; we had spent a good deal of energy arguing with them; some of us had been them. Thus, we knew where their nerves were most exposed and their hypocrisy most naked.” In short, they were responding to the leftward lurch of the Democratic Party, Ted Kennedy having in effect usurped the position John Kennedy once held.

The neocons intuited, for example, that Fidel Castro and Che Guevara had “been taken for the kind of romantic revolutionary heroes that leftist lady newspapermen dreamed of sleeping with, and that the men of the radical movement longed to emulate.” That’s getting at the “personal” behind the “political.” What, speaking of those bearded “romantic revolutionary heroes,” was the American government going to do about “the spread of Communism into our very own neighborhood”? When it became evident that Ronald Reagan, unlike his opponent Jimmy Carter in 1980, would oppose that spread, a cohort of Democrats, Jeane Kirkpatrick among the foremost, came out for the Republican candidate.

By way of example, I’ll devote the remainder of my small space to Midge’s way of understanding the battle of the sexes, the stuff of what, in the long history of literature, has been called the marriage plot. We’ve all seen the Rosie the Riveter poster in Women’s Studies offices. Rosie, as Midge noted, “would undoubtedly have been astonished at the thought that some thirty years later she would turn up as a kind of icon for educated young women who would deplore the fact that [after the war] she had been required to take off her bandanna and go back home.” In fact, she wanted to go home to her husband and children, something nearly everyone thought “a good thing to do”—the quicker the better. The Decters were in this very like their neighbors: “one day they were necking on a blanket at Jones Beach, and the next they were stuck in four small rooms with three babies.”

It wasn’t a social construct, some robotic movement prompted by subliminal messages from business and government. It was their generation’s turn to play—freely choose to play—the transhistorical game, in which, as Midge said,

men pursue and women decide whether or not to surrender . . . a game that is especially hazardous for a woman to lose, for sex makes babies, and she needs her babies to be fathered. In the end, she offers [the man] an unspoken deal: you cleave unto me, forsaking all others, and be father to my babies, and I promise that I will repay this violation of your sexual nature, which is to be promiscuous, by making you a home and in other ways making it worth your while.

The battle of the sexes: the naturally monogamous woman subdues the naturally promiscuous man, and civilization, built upon the family, rejoices in her victory. The sexual and feminist revolutions of the 1960s, which pretended that “men and women are alike sexually,” turned the game from one settled by compromises, “in which everyone wins,” to one “with no rules in which everyone loses.”

Look at how college students are now compelled to live. Lacking external prohibitions as to where they’re to sleep, shower, brush their teeth, and so on, the young women pretend their “autonomy” is being violated at all points, while “the unacknowledged truth is that most of them do not wish to sleep around, and they do not wish to be granted permission to do so.” No one, including parents, teachers, and administrators, is being anti-permissive, save in the “woke” arena of speech with all the things you can’t say. It’s why young women sometimes “cry ‘rape’ when they know full well that they have not been raped because deep down they feel that the world around them has denied them the means to resist in any other way.”

That is, while they don’t want to sleep around, all the signals in the dorm, which under ordinary circumstances might “very well be more of a sexual turnoff than a provocation,” say they’re supposed to sleep around. And we owe this to the adults, parents, and college administrators, who no longer wish to be in charge because they lack faith in the principles their authority once rested on. They’ve told the kids they’re on their own: scarcely anything’s mandated or forbidden, and nearly everything’s permitted.

It’s perhaps the young men, Midge thought, whom we should most worry about. In elementary school, boys’ restlessness is often drugged down; in high school, their humanities classes teach them that masculinism—in war, in marriage, everywhere—is the font of all our woes; and there’s more of the same in college, if they even bother to go. Where can they innocently test their manliness? “The last thing an American boy is nowadays apt either to hear or to read,” she observed,

is that girls, being the weaker and more delicate sex, need to be protected. Anyone who tried to tell them such a thing would, of course, instantly be set upon by a gender posse. Thus, many of them grow up feeling not brave with girls but, on the contrary, some unexpressed combination of clumsy and resentful.

The good people who have written obituaries have rightly said we’ll miss Midge Decter. So, if they but knew it, will our children and grandchildren.

Image: Courtesy of YouTube.