John S. Rosenberg blogs at www.Discriminations.us. He last appeared in AQ in summer 2019 with “Harvard Hoist On Its Own Petard?”

Progressives fear, and conservatives eagerly anticipate, learning the fate of affirmative action when Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard College reaches the Supreme Court. Both this pessimism and optimism are misguided, however, since affirmative action as we have known it is dying no matter what the Supremes decide. Some dark hints of what the future holds are provided by an executive order on racial “equity,” signed by President Biden on his first day in office, that reads as though it was written by the central committee of Black Lives Matter.

Since the post-George Floyd protests and Black Lives Matter/Antifa riots of last summer the left has become increasingly insistent about the need to “do more” to eliminate what it sees as “systemic racism”—a demand that implicitly, and often explicitly, rejects as woefully inadequate the results of what is by now almost fifty years of affirmative action. And the often-dormant resolve of conservatives and others to resist racial preference policies has been aroused by the decisive rejection of Proposition 16 by California voters, the attempt of Democrats to repeal Proposition 209 and revive affirmative action in that state. The gap between elites and popular opinion, between left and right, between Democrats and Republicans, is perhaps wider on this issue than any other. There are virtually (maybe actually) no elected or appointed Democrats in federal or state government remaining who believe it is necessary for the state to treat citizens “without regard” to race or ethnicity.

Thus even if affirmative action remains as a label, its substance is sure to change. This change will not be the first it has undergone. In fact, perhaps we should start to think of its next phase as Affirmative Action: Release 3.0.

As specified in both of its foundational documents—President Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925 (1961) and President Johnson’s Executive Order 11246 (1965)—“affirmative action” originally meant taking steps to ensure colorblind equal opportunity “without regard to race, creed, color, or national origin.”

The early transition from “without regard” colorblindness to “race conscious” preferential treatment is widely believed to have been heralded by President Lyndon Johnson’s Commencement Address at Howard University, June 4, 1965. “Freedom is not enough,” he proclaimed.

You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, “you are free to compete with all the others,” and still justly believe that you have been completely fair….We seek not just legal equity but human ability, not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result.

I believe the conventional wisdom that at Howard President Johnson called for abandoning “without regard” colorblindness in favor of race-based preferential treatment is mistaken. What he meant by “equality” continued to be non-discriminatory equality of opportunity. The very next sentence in Johnson’s speech, for example, states: “For the task is to give twenty million Negroes the same chance as every other American.”

But whatever Johnson himself meant or intended, the “without regard” principle was in fact soon abandoned in favor of race-conscious preferential treatment. Now there is increasing evidence that given the rapid spread of “cancel culture” and newly “woke” attitudes on race throughout academia and beyond, our current version of affirmative action is already seen, to use President Johnson’s words, as “not enough, not enough.” If, as the woke insist, our society is poisoned by a pandemic of endemic, systemic, structural racism, then it follows that our fifty years of affirmative action in higher education and elsewhere have been an abject failure, a failure that is now widely asserted.

Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars, has recently skewered the “mandatory banality” of statements from an array of university presidents in the wake of the post-George Floyd protests and riots. But there is more in these statements, and similar ones by faculties, than banality. They also share an obsequious tone of groveling apologia for the failures of their institutions to root out racism—an implicit (and in the case of Princeton, as we shall see below, explicit)—acknowledgment of the failure of the affirmative action they all have practiced for decades.

The University of New England’s June 2020 “statement on anti-racism” says it plainly: “We have a moral obligation to do better.” Other universities and colleges followed verbatim:

University of Wisconsin, Oskosh: “We must do better.”

University of Tennessee Chancellor Donde Plowman: “We must do better.”

Ursinus College President Brock Blomberg: “We must do better.”

What Does “Doing Better” Mean?

When it comes to recognized protected groups American colleges and universities are the most unctuously deferential institutions in the country. But whatever else “doing better” means, it appears that there is virtually (maybe actually) unanimous agreement across higher education that fifty years of affirmative action was “not enough, not enough.” The specifics vary from campus to campus, but with what sounds like one obeisant voice faculties and administrations across the country call for new and often far-ranging efforts to admit more black applicants and hire more black faculty—not under the umbrella of non-discrimination or affirmative action, but in the name of “equity,” “inclusion,” and “antiracism.”

The mother of all faculty statements, the one issued by 400 members of the Princeton faculty, lays out a very specific, comprehensive list of chapter and verse demands, and adopts the style of capitalizing “black” to show compliance with the so called anti-racism agenda.

The statement begins with the bald assertion that “Anti-Blackness is foundational to America,” which could have been lifted from the New York Times’s 1619 Project that eminent Pulitzer prize-winning Princeton historian James McPherson (who did not sign the faculty letter) so effectively criticized.

And not just America, since the Princeton 400 declared that anti-blackness also “plays a powerful role at institutions like Princeton,” despite declared values of diversity and inclusion. “Anti-Black racism has a visible bearing upon Princeton’s campus makeup and its hiring practices,” the letter states, and calls on the University “to take immediate concrete and material steps to openly and publicly acknowledge the way that anti-Black racism, and racism of any stripe, continue to thrive on its campus . . . We call upon the University to amplify its commitment to Black people and all people of color on this campus as central to its mission, and to become, for the first time in its history, an anti-racist institution.”

The letter’s 4,200 words provide a detailed blueprint of what an “anti-racist” institution should look like. It is both too comprehensive and too detailed even to summarize, but it would not be unfair to say both its substance and spirit parrots Black Lives Matter. Here are a few examples:

- Reward and punish departments based on black hiring.

- Give seats at your decision-making table to people of color who are actively anti-racist and inclusive in their practices.”

- Redress the demographic disparity on Princeton’s faculty immediately and exponentially by hiring more faculty of color.”

- Engage an outside committee” of “experts in the study of race and challenging racism . . . from communities of color” and do what it says.

- Form an internal committee of faculty and students of color to whom the University, in carrying out this work, remains accountable.”

- Elevate more faculty of color to prominent leadership positions within divisions and across the University.”

Some demands are quite specific—“Nominate no fewer than two faculty members of color” to several named committees. Others raise serious academic freedom issues, such as specifying the research direction of a new hire—“Fund a chaired professorship in Indigenous Studies for a scholar who decenters white frames of reference.”

Perhaps most troubling of all is the demand to monitor faculty teaching and research much in the fashion of Soviet commissars to root out any examples of what the monitors regard as racism: “Constitute a committee composed entirely of faculty that would oversee the investigation and discipline of racist behaviors, incidents, research, and publication on the part of faculty . . . ”

It is clear that what university administrations and faculties intent on “doing better” now seek is a far cry from affirmative action as it has been defended and practiced for the past fifty years. No longer will race be regarded, either verbally or in fact, as just “one factor among many” to be considered in a “holistic” review of the whole person.

Emblematic of this new view is Princeton classics professor Dan-El Padilla Peralta, one of the primary organizers of the Princeton faculty letter. After being accused from the audience of being an affirmative action hire after his presentation at a meeting of classicists, he asserted in a subsequent article that “I should have been hired because I was black: because my Afro-Latinity is the rock-solid foundation upon which the edifice of what I have accomplished and everything I hope to accomplish rests.” (Emphasis in original)

In an Open Letter to the University community last September Princeton President Christopher Eisgruber announced plans to combat the systemic racism that persist at Princeton. “Racist assumptions from the past,” he acknowledged, “remain embedded in the structures of the university itself.” His solutions reflected the race-based demands of the faculty letter, such as assembling “a faculty that more closely reflects both the diverse makeup of the students we educate . . . To that end, we will undertake enhanced efforts to expand diversity of the faculty pipeline, and aspire to increase by fifty percent the number of tenured or tenure-track faculty members from underrepresented groups over the next five years.”

President Eisgruber’s admission of pervasive systemic racism at Princeton provoked the U.S. Justice Department into launching an investigation, since Princeton had affirmed many times in applying for federal funds that it did not discriminate. This in turn led eighty college presidents to write a letter opposing the DOJ investigation, arguing in effect (with unintended humor) that just because a university admits to systemic racism embedded in its structures doesn’t mean it discriminates against anyone. Can racism really be systemic, one is tempted to ask, if it produces no discrimination?

As a measure of how far we have traveled almost overnight from affirmative action as it has been, consider Stanford’s August 2019 Equal Employment Opportunity Statement signed by the president. First, it gives lip service to the traditional but even then discarded notion of non-discrimination: “To encourage . . . diversity, we prohibit discrimination and harassment and provide equal opportunity for all employees and applicants . . . regardless of race, religion, color, national origin.”

President Tessier-Lavigne recognized, as did President Johnson in 1965, that “a simple policy of equal employment opportunity may not be sufficient by itself to attract a diverse applicant pool,” but note well what follows: “The University does not sacrifice job related standards when it engages in affirmative action. The best qualified person . . . must always be hired; that is the essence of equal opportunity. Affirmative action simply asks us to cast our net more widely to broaden the competition.”

If a university president gave a speech today endorsing the sort of affirmative action reaffirmed by Stanford President Tessier-Lavigne in 2019, he would be denounced, possibly even investigated, for saying the equivalent of “all lives matter.” (The University of California administration has already promulgated that “I believe the most qualified person should get the job” constitutes a microaggression.1) Just as colorblind non-discrimination came to be denounced in progressive circles as racist, so too will the sort of affirmative action practiced for the past fifty years.

In fact, that has already begun. Colorblindness and opposing racial favoritism are now widely denounced in progressive circles as a shibboleth of white supremacy. “Colorblind” and “neutral” are “counterproductive to antiracist work,” according to one propagandistic teaching aid. Race-based decisions are no longer disguised; they are advertised, with the demands of the 400 Princeton faculty members a good example. Thus the University of Chicago English Department is limiting next year’s entering graduate students to those devoted to black studies. Syracuse University is increasing funding to hire minority professors. Students and their faculty advisor at the University of Rhode Island, asserting in clumsy language that there has been a “deliberate and racist demonizing exclusion of highly qualified African Americans/Blacks, Latinos/Hispanics and Native Americans from positions of senior leadership and other positions throughout the university," are demanding that “the next President of the University of Rhode Island must be an African American with a lineage to slavery.”

From Affirmative Action to Antiracism . . . or Not

The high priest of this turn from “diversity” justified affirmative action to an unapologetic promotion of pro-black discrimination is Ibram X. Kendi, whose How To Be An Antiracist (2019) is its bible. “The language of color blindness—like the language of ‘not racist’—is a mask to hide racism . . . The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination,” he writes. “The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.”

As Kendi stated in another of his books, racial disparities are not evidence of possible racial discrimination; they “must be the result of racial discrimination.” And by “racial disparities,” he emphasized, “I mean how racial groups are not statistically represented according to their population.” Thus, according to this antiracist view, the obvious and only cure to the systemic racism revealed by racial disparities is to implement proportional representation.

Universities, large corporations, and other elite-dominated institutions—all eager to demonstrate their antiracist bona fides by frantically hiring more minorities—apparently are more than willing to turn to quotas, but there are some serious obstacles facing this approach.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the legal obstacle may be the least serious. True, current civil rights law, even as “liberally construed” by the courts, frowns on quotas (that’s why quota mongers take such care to disguise them with obfuscatory rhetoric about “diversity”), but there is good reason to believe that the Democrats in Congress will seize their first opportunity to rewrite those laws and/or pack the Supreme Court. Substantial packing may not even be necessary, since a Court that can stretch “equal protection” to legitimize racial preference to promote “diversity” should have no problem concluding that correcting “disparities” also passes muster.

A potentially bigger obstacle to the widespread implementation of the antiracist call for proportional representation is the fact that by substantial margins the public opposes it. In “ The Harvard Affirmative Action Case and Public Opinion,” Frank Newport, then Gallup’s editor in chief, quoted a question Gallup asked four times between 2003 and 2016:

Which comes closer to your view about evaluating students for admission into a college or university: applicants should be admitted solely on the basis of merit, even if that results in few minority students being admitted (or) an applicant’s racial and ethnic background should be considered to help promote diversity on college campuses, even if that means admitting some minority students who otherwise would not be admitted?

“Each of the four times Gallup has asked this question over a thirteen-year time period,” Newport emphasized, “between 67 percent and 70 percent of Americans chose the ‘solely on merit’ option.”

Similarly, in 2019 the Pew Research Center asked respondents whether they thought employers should “only take a person’s qualifications into account, even if it results in less diversity,” or whether they should “take a person’s race or ethnicity into account, in addition to qualifications, in order to increase diversity.” Seventy-four percent of all adults said qualifications only, including 54 percent of blacks and 69 percent of Hispanics. Pew also asked respondents whether they thought race or ethnicity should be a major factor, a minor factor, or no factor in college admissions. Seven percent thought it should be a major factor, 19 percent a minor factor, and 73 percent not a factor at all.

And that opposition was to the milder version of racial preferences ( in comparison to hard quotas), not the rigid proportional representation demanded by the antiracists.

Still, even though this opposition to race-based preferential treatment is substantial, I described that opposition as only potentially an obstacle to quotas because that opposition has long been present and yet it has not often blocked preferential treatment, which for some time now has actually been enforced through outright quotas, as the Harvard case brought to light. That could change if Republican politicians ever develop the courage to appeal to this strong majority sentiment, but so far they have not done so.

A more serious obstacle to implementing quotas is that doing so would have some troubling, unforeseen (to antiracists) consequences and might well threaten something approaching an ethnic civil war.

Look, for example, at the “disparities” in admission to the University of California at Berkeley that so agitate the antiracists:

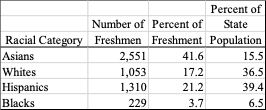

Table 1: University of California Berkeley

Fall 2020 New Students by Race

Sources: University of California Berkeley; U.S. Census.

Contrary to widespread misunderstanding, the most “underrepresented” racial or ethnic students among entering Berkeley freshmen in 2020 were whites, at 47 percent of what Kendi and the antiracists regard as equity or parity, i.e., a number equal to their proportion of the California population. By contrast, Hispanics are at 54 percent, blacks 57 percent, and the “overrepresented” Asians are at a whopping 268 percent.

To make their numbers reflect their 6.5 percent proportion of California’s population, the number of black entering freshmen would have to be increased from their current 229 to 398, an increase of 74 percent.The number of Hispanics, 1,310, would have to increase to 2,413, or by 84 percent. Whites would have to increase from 1,053 to 2,235, a 112 percent increase. The most dramatic effect of imposing proportional representation on the University of California would be a draconian reduction in the number of Asian freshmen: from 2,551 to 949, a decrease of 63 percent.Berkeley’s total 2020 undergraduate numbers vary in some details but tell the same story, as do the fall 2020 enrollment numbers from the entire University of California system.

Nor is California unique. Washington state has also experienced pitched battles over affirmative action, banning it by referendum in 1998 and defeating a duplicitous attempt to bring it back in November 2019, an effort led by a hardy band of underfunded Asians.

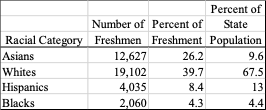

As in California, Washington elites and activists both demanded a return to racial preferences in order to cure “disparities,” but fall 2020 data on enrolled students at the University of Washington tell a different story:

Table 2: University of Washington

Fall 2020 New Students by Race

Sources: University of Washington; U.S. Census.

In Washington as in California, blacks have the lowest “disparity” and whites the highest. To reach parity with their proportion of the Washington state population, the numbers of blacks, Hispanics, and whites would have to be increased—by 3 percent, 55 percent, and 70 percent respectively—and the number of Asians would have to be reduced by 61 percent.

Presumably in pursuit of “equity,” the Fairfax County School Board has recently changed the admission policy for Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (TJ), often referred to as the best high school in the United States. TJ’s current students are 73 percent Asian, 17.7 percent white, 3.3 percent Hispanic, and 1 percent black. In a lawsuit filed by the Pacific Legal Foundation, the plaintiff’s estimate that the new policy would result in a student body that is roughly 30 percent Asian, 5 percent black, 8 percent Hispanic, and 48 percent white. Is white the new color of “equity”?

Affirmative Action’s Future Will Not Resemble Its Past

It would be interesting to hear Prof. Ibram X. Kendi explain to his antiracist acolytes in academia, corporations, the media, and the Democratic Party exactly why he favors eliminating “disparities” by imposing proportional representation when doing so would increase the numbers of Hispanics and whites much more than blacks—almost as interesting as hearing him explain to Asians why it is good for their numbers in selective institutions to be cut by over 60 percent.

Even if the Supreme Court does not drive a nail in the coffin of affirmative action, and even if whites, mysteriously, continue to accept passively holding the short end of the racial preference stick, Asians in New York City, Washington (defeating I-1000), and California (defeating Proposition 16) have demonstrated that they are increasingly unwilling to be sacrificed so that a few whites can be exposed to more blacks and Hispanics.

In the past the conflict over affirmative action was between critics who believed in colorblind equality and supporters who, while giving lip service to the principle of equal treatment, favored putting what they claimed is an ever-so-light thumb on the scale to reduce the number of whites and increase the numbers of blacks and Hispanics. Now an increasingly influential segment of elites and progressives reject the principle of equal treatment altogether.

In his book For Discrimination, for example, Harvard Law Professor Randall Kennedy argues that racial preference should not be “presumptively illegal,” that “nondiscrimination is better understood not as a ‘principle’ but merely a tool,” and that the argument of Hubert Humphrey and others “forswearing affirmative action” in the debates over the 1964 Civil Rights Act “should be understood as mere strategic feints” reflecting the limitations of “early 1960s white racial liberalism.”

As Wenyuan Wu, executive director of Californians for Equal Rights, the organization that led the successful effort to defeat Prop. 16, has observed, “While ‘old-fashioned’ proponents of race-based affirmative action still pay lip service to principles of unity and equality, the new generation of ‘racial reckoning’ foot soldiers are most interested in demolishing all Western institutions and rebuilding America on a bifurcated vision of oppressors vs. victims." The new antiracist affirmative action has abandoned not only the principle but also the goal of colorblind non-discrimination altogether.

1 Eugene Volokh, “UC’s PC police,” Los Angeles Times, June 23, 2015.

Image: Andreas Praefcke, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, cropped.

Recommended Citation: John S. Rosenberg (2021), Affirmative Action: R.I.P. or Release 3.0?. 34(2) DOI: 10.51845/34su.2.7. https://www.nas.org/academic-questions/34/2/affirmative-action-rip-or-release-3.0.