Executive Summary

In 1955, the state of Texas enacted a legislative requirement that students at public institutions complete two courses in American History. In 1971, the legislature officially incorporated the requirement into the Texas Higher Education code. With that mandate in mind, the Texas Association of Scholars and the National Association of Scholars’ Center for the Study of the Curriculum proposed to determine how students today meet the requirement, and what history departments offer as a means of doing so. What courses can students take, and what vision of U.S. history do those courses present? This study is the result of our investigation.

Our report focuses on the University of Texas at Austin (UT) and Texas A&M University at College Station (A&M), flagship institutions serving large undergraduate populations. For this study we examined all 85 sections of lower-division American history courses at A&M and UT in the Fall 2010 semester that satisfied the U.S. history requirement. We looked at the assigned readings for each course and the research interests of the forty-six faculty members who taught them. We also compared faculty members’ research interests with the readings they chose to assign.

We found that all too often the course readings gave strong emphasis to race, class, or gender (RCG) social history, an emphasis so strong that it diminished the attention given to other subjects in American history (such as military, diplomatic, religious, intellectual history). The result is that these institutions frequently offered students a less-than-comprehensive picture of U.S. history. We found, however, that the situation was far more problematic at the University of Texas than at Texas A&M University.

We classified course readings by how much they focused on race, class, and gender. Course sections with half or more of their content having an RCG focus were classified as high; those with 25 to 49 percent having an RCG focus were classified as moderate; and those with less than 25 percent having an RCG focus were classified as limited. We classified faculty members assigning primarily high RCG readings as “high assigners” of RCG materials.

Major Findings:

• High emphasis on race, class, and gender in reading assignments.

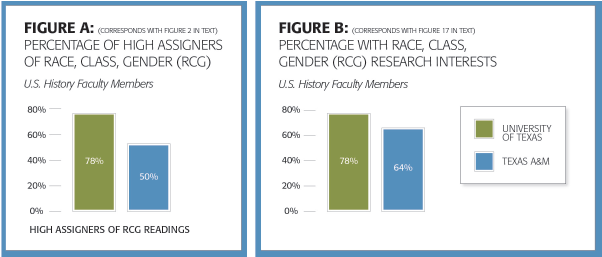

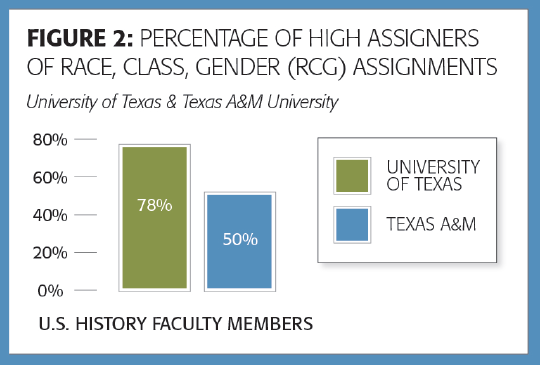

78 percent of UT faculty members were high assigners of RCG readings;

50 percent of A&M faculty members were high assigners of RCG readings.

• High level of race, class, and gender research interests among faculty members teaching these courses

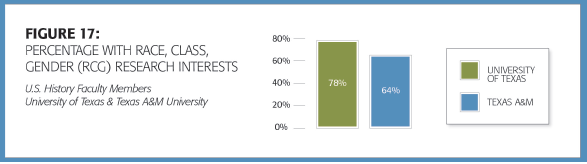

78 percent of UT faculty members had special research interests in RCG;

64 percent of A&M faculty members had special research interests in RCG.

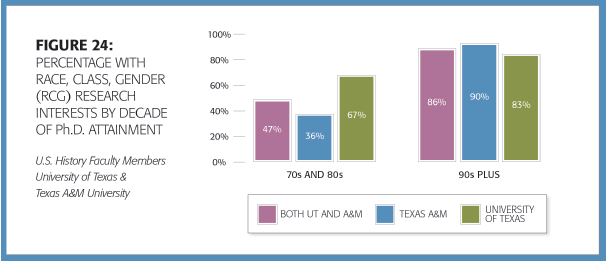

• More recent Ph.D.s are more likely to focus research on race, class, and gender

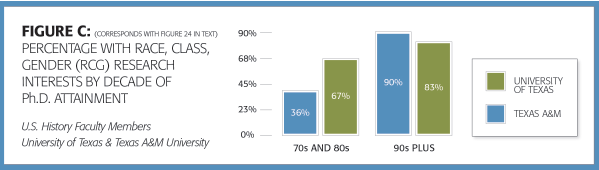

83 percent of UT faculty members teaching these courses who received their Ph.D.s in the 90s or later had RCG research interests, while only 67 percent of UT faculty members who received their Ph.D.s in the 70s or 80s had RCG research interests.

90 percent of A&M faculty members teaching these courses who received their Ph.D.s in the 90s or later had RCG research interests, while only 36 percent of A&M faculty members who received their Ph.D.s in the 70s or 80s had RCG research interests.

There were institutional differences in the associations between research interests and reading assignments. At A&M, those with RCG research interests were significantly higher assigners of RCG reading assignments than those without such RCG research interests. On the other hand, there was no such relationship at UT. At UT, both RCG and non-RCG research-focused faculty members were predominately high assigners of RCG readings.

The extent to which UT faculty members gave high assignments of RCG readings—whether or not they had special RCG research interests, and regardless of when they received their Ph.D.s—suggests that the culture in an institution and its history department plays a greater role than other factors in influencing reading assignment choices. Additionally, a much higher percentage of UT faculty members teaching survey courses made high RCG assignments than survey course teachers at A&M.

An inordinate focus on RCG isn’t the only problem. As RCG emphases crowd out other aspects and themes in American history, we find other problems setting in, including the narrow tailoring of “special topics” courses and the absence of significant primary source documents. Special topics courses used by students to fulfill the history requirement lack historical breadth; they seem to exist mainly to allow faculty members to teach their special interests. In those courses and in more general courses, too, faculty members failed to assign many key documents from American history, for example, none of them assigning the Mayflower Compact or Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. Only one faculty member assigned the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” and only one assigned Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville. Moreover, rarely did reading assignments contain anything about figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Dewey, Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas A. Edison, the Wright brothers, or the scientists of the Manhattan Project.

These trends extend beyond the two flagship Texas universities. History departments at other universities around the United States share similar characteristics, such as faculty members’ narrow specializations; high emphasis on race, class, and gender; exclusion of key concepts; and failure to provide broad coverage of U.S. history.

If colleges and universities are to provide students with full and sound knowledge of American history, some things need to change. Teachers of American history should take race, class, and gender into account and should help students understand those aspects of our history, but those perspectives should not take precedence over all others.

We Offer Ten Recommendations:

1. Review the curriculum. History departments should review existing curricula, eliminate inappropriate over-emphases, and repair gaps and under-emphases.

2. If necessary, convene an external review. If history departments are unwilling to undertake such a review, deans, provosts, or trustees need to consider an external review.

3. Hire faculty members with a broader range of research interests. Hiring committees should employ new faculty members who have a solid understanding of the broad narrative of American history.

4. Keep broad courses broad. Survey and introductory courses should give comprehensive overviews.

5. Identify essential reading. As a safeguard against overlooking essential material, history department members should collaborate to develop lists of readings that the department expects students at a given course level to study.

6. Design better courses. Departments should promote the development of courses that contribute to a robust, evenhanded, and reasonably complete curriculum.

7. Diversify graduate programs. Graduate programs in U.S. history should ensure that they do not unduly privilege themes of race, class, and gender.

8. Evaluate conformity with laws. Other states should enact laws similar to the Texas requirement that students complete two courses in American history, but better accountability is needed to ensure that colleges’ teaching lines up with legal provisions.

9. Publish better books. Publishers should publish textbooks and anthologies that more adequately represent the full range of U.S. history.

10. Depoliticize history. Historians and professors of United States history should counter mission creep by returning to their primary task: handing down the American story, as a whole, to future generations.

Introduction

Americans are increasingly disconcerted by the gap between the credentials of college graduates and the learning they have actually acquired over four or more years of undergraduate study. A student who earned an “A” in freshman composition, they find, may not write very well. Employers complain that recent graduates don’t possess adequate workplace skills, while national surveys uncover deficits in basic knowledge of history, science, and civics.

This report zeroes in on one field, American history, as it was presented in freshman and sophomore history courses at the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M at College Station, the two largest public campuses in the state, during the fall semester of 2010.

We reviewed the reading assignments and research interests of the faculty members teaching these courses. What we found all too often was an inordinate emphasis on issues of race, class, and gender, a focus that, far from expanding and diversifying knowledge of U.S. history, presents a constrained version of the past. We found, however, that the situation was far more problematic at the University of Texas than at Texas A&M University.

Background

We focused on the Texas examples because of the relatively good accessibility of data. In 1955, the Texas Legislature enacted a law that requires all students at public higher education institutions to complete two courses in American History.1 This provision was later in 1971 incorporated into the official Texas Higher Education Code. The most relevant regulation implementing this law2 contains the following stipulations:

1. Courses in this category focus on the consideration of past events and ideas relative to the United States, with the option of including Texas history for a portion of this component area.

2. Courses involve the interaction among individuals, communities, states, the nation, and the world, considering how these interactions have contributed to the development of the United States and its global role.

The law obliges history departments in public universities to offer a sufficient number of relevant sections to allow students to fulfill the requirement. The stated intention of the legislation was to increase general civic awareness and the civic knowledge of college graduates. In 2009, the Texas Legislature enacted another law that requires universities to make public the backgrounds, research interests, and course assignments of faculty members. The same law, HB2504, requires that the syllabi of all courses be reachable within “three clicks” of the institution’s home page.

Taken together, these legal provisions mean that public universities in Texas must provide all students with courses in American history, and that we can find out a substantial amount about who actually teaches these courses and how they are taught. The availability of such a range of information is highly unusual in American higher education, even for public universities. The Texas situation presents an opportunity for systematic analysis. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to take full advantage of the chance to go beyond the mere listing of courses in a college catalog to offer a close examination of the content of the courses and the scholarly interests of the faculty.

General Procedures

While lower-division courses in math and physical science have a predictable content—organic chemistry covers pretty much the same material no matter who teaches it—American history content can vary widely from course to course. Depending on the choices made by those who teach them, one course might highlight one period over another, while another might favor political topics over social or economic ones, or vice versa.

Since for most students these courses provide the only exposure they will ever get to college-level American history, these variations are important. The major purpose of this report is to examine them. To do this, we divided course readings and faculty interests into 11 broad content categories well established in the discipline (for full definitions of these categories see Appendix 3):

• Diplomatic and International Relations History

• Economic and Business History

• Military History

• Philosophical and Intellectual History

• Political History

• Religious History

• Scientific, Environmental, and Technological History

• Social History with Gender Emphasis

• Social History with Racial and Ethnic Emphasis

• Social History with Social Class Emphasis

• Social and Cultural History - Other

We examined 85 course sections offered during the fall semester of the 2010-2011 academic year; the courses were taught by 46 faculty members. These comprised all of the lower-division American history courses—and faculty members teaching them—that satisfied the legislative requirement in American history at the University of Texas and Texas A&M University during that semester. These courses are of three distinct types: general American history survey courses, Texas history courses, and a group of“special topics” American history courses. We collected all the reading assignments in the 85 courses as well as the curricula vitae of the 46 teachers.

We analyzed the syllabus of every lower division American history section. We looked at the content of the assigned textbooks and supplemental readings. We also examined the curriculum vitae of each of forty-six faculty members teaching American history courses that satisfied the statutory requirement. We compared their research interests with the types of books they assigned. We also gathered information on faculty members’ ranks and the years of their highest degree. (A copy of every course syllabus and vitae examined in this study is contained in a separate file available online.)3

Students4 taking these courses were generally not history majors but undergraduates fulfilling their general education requirements while meeting the statutory mandates.

Main Findings

Our principal finding is that in meeting the Texas state requirement, the University of Texas and Texas A&M history departments offer a range of lower-division courses that all too often favors one kind of historical study: one that emphasizes race, class, and gender (to which we refer in the report with the abbreviation RCG), and de-emphasizes other approaches such as political, intellectual, economic, diplomatic or military history, or comprehensive survey courses. We do not mean that race-class-gender (RCG) courses or readings are the only options available to freshmen and sophomore students at these two universities: the situation is more complex, and the University of Texas and Texas A&M differ from each other in some pertinent details.

Race, class, and gender are important topics in American history, of course, but few knowledgeable observers would conclude that a college-level introduction to American history with such a strong emphasis on these themes does justice to the larger topic. The number of topics and the depth to which they can be examined in a history course is limited by the number of classroom hours and the amount of material students are expected to read and comprehend. Thus a focus on one set of themes inevitably means less attention to other themes.

Our study shows that the preference for RCG course content, however, is real and substantial. We classified course readings in terms of how much they focused on race, class, and gender. Those course sections with half or more of their content having an RCG focus were classified as high; those with 25 to 49 percent having an RCG focus were classified as moderate; and those with less than 25 percent having an RCG focus were classified as limited. We then classified faculty members assigning primarily high RCG readings as “high assigners” or “high users” of RCG materials.

We examined the data to find out whether there was an association between research interests and reading assignments. An overemphasis on RCG readings contributed to the relatively scant attention that was paid to fundamental documents and texts of American history. Tocqueville’s Democracy in America and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, for instance, were rarely assigned in American history survey courses at these two universities; and numerous political documents, such as the Mayflower Compact and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, were not assigned in any American history courses.

Our analysis shows that the history courses provided by the University of Texas and Texas A&M often fall short of the spirit of the law, and students are frequently not offered a comprehensive and pluralistic interpretation of our nation’s past. Many meet their American history requirement by taking courses that focus on content that makes it impossible to grasp the larger political conflicts, institutional frameworks, and philosophic ideals that have governed the course of American history.

In general, RCG research interests appear to find more favor among American history faculty members at the University of Texas than at Texas A&M. A difference in atmosphere between the two departments may explain why at UT even faculty members without specified RCG interests assigned RCG-themed textbooks and supplementary readings.

Associations

There was a near-perfect relationship between teaching an RCG-themed special topics course and having an RCG research interest. It is through these courses that the strong RCG research interests of faculty members at the University of Texas are most manifest in teaching. There was a far less clear relationship in the survey courses between RCG research interests and RCG assignments, with differences between institutions. At Texas A&M, those with RCG research interests were significantly higher assigners of RCG reading assignments than those without such RCG research interests. On the other hand, there was no such relationship at the University of Texas.

We identified a strong association between RCG assignments and stage of career, with higher assignment rates among those with more recent Ph.D.s at both institutions. We conjecture that this pattern of assignment rates reflects the departmental culture, both in the department as a whole and in the instructor’s seniority cohort. As the proportion of faculty members with RCG interests in the relevant group grows, all instructors in the group may become more likely to assign a preponderance of RCG materials to their students. Unlike Texas A&M, UT appears to have already reached the critical mass of RGC faculty within the department as a whole; this seems to have created the atmosphere encouraging faculty to adopt RCG textbooks and supplemental readings.

Conclusions

There is, of course, no single formula for good history teaching, nor should there be. Nor is it a bad thing that faculty members differ in the overall assessment of what is most significant and worthy about the American story. Students benefit from a variety of views and approaches. If they have different instructors in different courses, they come to see the multi-sidedness of historical events. And even if they don’t, they can acquire fresh perspectives on American history from other students who have. Diversity of informed opinion makes a university a better place to teach and learn. A history department too narrow or monolithic in its course offerings or views can intellectually shortchange its students and faculty.

Unfortunately, American history at UT and, to a lesser extent, at A&M, fall into the latter condition. Both departments have raised the emphasis of RCG themes in the teaching of U.S. history, at the same time downgrading other history discipline perspectives. The result has been a narrowing conception of our nation and the elevation of racial, class, and sexual identity into the central story of America. Other matters—individual rights, entrepreneurship, industrialization, self-reliance, religion, war, science—fade into the margins along with the persons and events associated with them.

The results of this study provide evidence that this interpretation of American history is probably experienced by many students at the University of Texas and by a growing number at Texas A&M. In fact, the study suggests that Texas A&M has reached a dangerous tipping point in how students will be taught American history. This trend impoverishes U.S. history and it is inconsistent with the spirit of Texas law.

Our report also aims to address the larger question of how such broad gaps have appeared in American higher education between the ostensible subjects of study and what graduates actually know. General education in the United States—that component of a college education that focuses on the knowledge and skills that all graduates should acquire—is falling short of public expectations. We think that part of the explanation for that shortfall can be found in these pages. Broadly integrative approaches to core subjects and comprehensive surveys have been displaced by narrow, specialized, and ideologically partisan approaches, largely driven by faculty research agendas. This study offers a fine-grained analysis of how that has happened in two major public universities.

We offer the model for other state universities as well as private colleges and universities that are concerned about the subtle ways a curriculum drifts away from its primary purpose.

Part I—Courses and Readings

Course Types

Eighteen faculty members at UT and twenty-eight at A&M offered courses that fulfilled the American history statutory requirements. The most frequently taught were those that formed the “Introduction to American History” sequence. At the University of Texas, the first course in this sequence (HIS 315K) surveyed U.S. history prior to 1865, while the comparable Texas A&M course (HIST 205) surveyed U.S. history prior to 1877. The second set of introductory courses (HIS 315L and HIST 206 respectively) brought the survey up to the contemporary period. Of the 46 faculty members we studied, 33 (72 percent of the total) taught one of these two surveys.

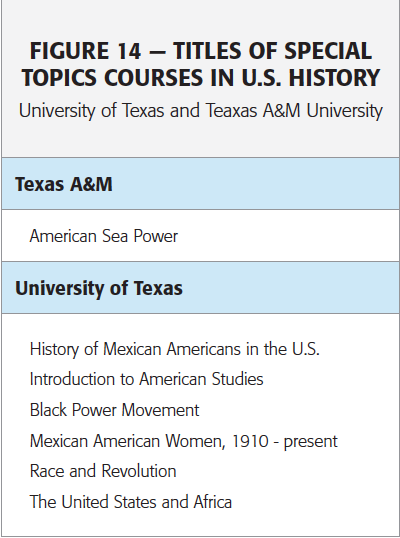

The percentage of faculty members teaching these two survey courses was higher at A&M than at UT. This is because UT offered more non-survey special topics courses focused on relatively narrow historical topics. Forty-four percent of the UT faculty members covered in our study taught a special topics course. These courses comprised 35 percent of the American history course sections offered there. UT offered six special topics courses and A&M offered one. The Texas A&M course was “American Sea Power.” The six at UT were titled:

• History of Mexican Americans in the US

• Introduction to American Studies

• The Black Power Movement

• Mexican American Women, 1910-Present

• Race and Revolution

• The United States and Africa

As is evident from their titles, most of the UT special topics courses5 were focused on race, ethnicity, or gender. It is noteworthy that the University of Texas placed these courses adjacent to the survey courses in the class schedule, implicitly encouraging students to regard them as serving equally to satisfy the American history requirement. By contrast, the one special topic Texas A&M course was clearly separated in the schedule numerically and physically from the survey courses. In addition, five A&M and two UT faculty members offered Texas history courses, which also partially satisfied the statutory requirements.

There was minimal overlap among the faculty members teaching the American history survey courses, special topics courses, and Texas history courses.6 A total of 85 separate American history sections at UT and A&M7 satisfied the statutory requirement.8

Overview of Reading Assignments

It is, of course, impossible to know everything that students experienced in these courses without information on the content of lectures, but it is reasonable to suppose that there is a relationship between class content and reading assignments. Accordingly, we concentrated on the reading assignments because we were able to review the syllabi and quantify their content.

In reviewing the syllabi of the American history courses taught at both campuses and taking duplications of readings into account, we tallied 625 individual reading assignments consisting of 499 titles.9 Every reading assignment on every syllabus was classified as belonging to one or several of our eleven discipline categories (see Appendix 3) with an additional miscellaneous category used for reading assignments that could not readily be fitted into a category. Textbooks were classified according to the extent to which they emphasized RCG content, with the assistance of an outside reviewer from the American Textbook Council. Another outside reviewer with a doctorate in political science and a specialty in political history read and initially classified all non-textbook titles based on the subject area content of the reading assignments. Two additional reviewers double-checked these classifications, assessing publishers’ notes and published reviews of the materials in question. None of the initial classifications were changed by these other readers, but some supplemental classifications were made whenever a secondary or even tertiary classification was deemed appropriate (in almost every case with the effect of increasing non-RCG designations).

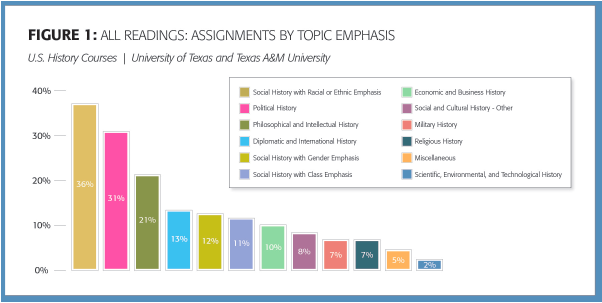

Figure 1 shows how the reading assignments in the survey, special topics, and Texas history courses were classified among the topic categories. It should be noted that 332 of the 499 titles came from six anthologies that were assigned by only seven faculty members teaching survey courses. The others, including those teaching Texas history, each relied on a textbook and only a few additional individual assignments. The faculty members of special topics courses taught without textbooks and anthologies, relying solely on individual reading assignments. Table 1 in Appendix 1 provides the data on topic emphasis of reading assignments, first for total reading assignments (that is to say, those from anthologies plus those assigned independently), second, for assignments that came from anthologies, and third, for those that didn’t come from anthologies, (that is to say, the universe of assignments to which most students would have been exposed) (Table 2 in Appendix 1 provides the data supporting each of the percentages in Table 1).

Our procedure aimed at capturing all reading assignments by all professors teaching these courses, and neither over-emphasizing nor under-emphasizing any particular reading.

Reading Assignment Emphasis Variations among Course Types

While reading assignments involving race or ethnicity emphasis accounted for 34 percent of the supplemental readings in survey courses, they represented 52 percent of Texas history assignments and 67 percent of special topics assignments (See Table 3 in Appendix 1). Gender-themed reading assignments were made most frequently in special topics courses, and class themes occurred most frequently in independently assigned readings in survey courses. The greatest overall thematic onesidedness occurred in UT’s special topics courses, but there was a strong overall RCG tilt in Texas history courses as well. On the other hand, in those survey courses where instructors drew assignments from an anthology, political, economic, intellectual, and diplomatic history themes were far better represented thematically.10

Overall Level of Reading Assignments Focused on Race, Class, and Gender

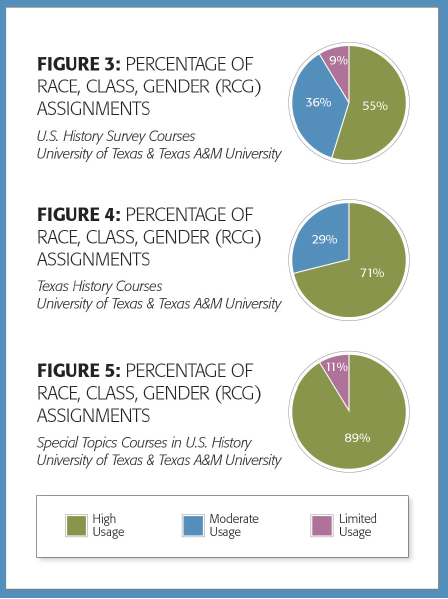

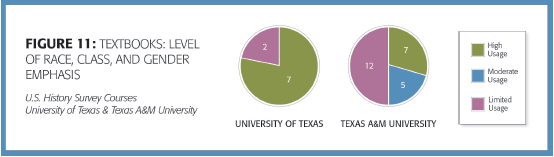

We reviewed the assignments made by each instructor to determine whether there was a high, moderate, or limited emphasis on RCG readings. Course sections with half or more of their content having an RCG focus were classified as high; those with 25 to 49 percent having an RCG focus were classified as moderate; and those with less than 25 percent having an RCG focus were classified as limited.

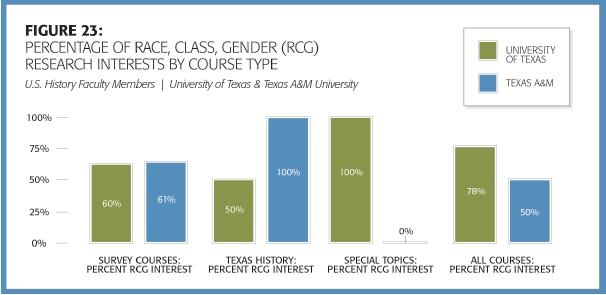

In Fall 2010, 78 percent of University of Texas faculty members who taught the freshman and sophomore history courses were high assigners of RCG readings, and 50 percent of the Texas A&M faculty members who taught these history courses were RCG high assigners. This is one of our central findings.

No adequate understanding of American history is possible without addressing questions pertaining to race and ethnicity, class, and gender, but when 50 percent or more of assigned readings emphasize these topics, there is reason to suspect that other important themes are getting short shrift. On the other hand, we would expect that many survey courses in American history would include a moderate use of race, gender or class reading assignments. Critical topics in American history, such as slavery, civil rights, industrialization, and the changing labor force would necessarily involve RCG reading assignments.

Sixty-one percent of the faculty members studied were RCG high assigners, UT having significantly more (78 percent) than A&M (50 percent). Thus, student exposure to a broad range of American history topics was more limited in the readings assigned at UT than at A&M. The differences are inflated because of UT’s special topics courses, which strongly emphasize RCG reading assignments. Breaking the courses down by category:

• Survey Courses: Of the 33 faculty members teaching these courses, 55 percent (18) were high assigners of RCG materials. At UT the figure was 60 percent compared to 52 percent at Texas A&M.

• Texas History Courses: Of the seven faculty members teaching these courses, 71 percent (five) were high assigners of RCG materials – both the two UT faculty members, and three of the five Texas A&M faculty members.

• Special Topics Courses: All eight of the UT faculty members teaching special topics courses were high assigners of RCG reading assignment. The one at Texas A&M, teaching military history, made no RCG assignments.

Survey Courses

Thirty-three faculty members taught a general survey course: twenty-three at Texas A&M and ten at the University of Texas. Most assigned a textbook plus three to five supplemental readings.

At UT, six out of the ten faculty members teaching general survey courses (60 percent) were high assigners of RCG readings. At A&M, 12 out of 23 faculty members teaching general survey courses (52 percent) were high assigners.

The emphasis on RCG topics and reading assignments in introductory American history survey courses at both institutions tended to crowd out attention to other aspects of history such as political, intellectual, economic, diplomatic, and military history. This is evident in the small number of courses whose reading assignments substantially addressed those areas. Without that breadth, it is impossible for the student who takes no other history courses to grasp the larger political conflicts, institutional frameworks, and philosophic ideals that have governed the course of American history.

| FACULTY # | HIGH USE | MODERATE USE | LIMITED USE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. History Faculty (Total) | 46 | 61% | 30% | 9% |

| A&M | 28 | 50% | 39% | 11% |

| UT | 18 | 78% | 17% | 5% |

| Survey Courses | 33 | 55% | 36% | 9% |

| A&M | 23 | 52% | 39% | 9% |

| UT | 10 | 60% | 30% | 10% |

| Texas History | 7 | 71% | 29% | 0% |

| A&M | 5 | 60% | 40% | 0% |

| UT | 2 | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Special Topics | 9 | 89% | 0% | 11% |

| A&M | 1 | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| UT | 8 | 100% | 0% | 0% |

Most of the reading assignments examined in this study were made by the 33 faculty members teaching survey courses (455 of the 625). Surprisingly, there was very little duplication among these assignments.

Apart from the special anthologies and textbooks, there were 93 individual reading assignments. Only 19 of them were duplicated by more than one faculty member, and only six were assigned by three or more.11 Even when the 332 assignments drawn from the six commercial anthologies are added, there is little overlap. When the anthologies are included, there were 11, rather than six, reading assignments that were assigned by three or more faculty members.12 The most frequently assigned reading was Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. But this assignment was made by only seven of the 33 faculty members teaching the survey course. Clearly, there is no common core of readings, something that might be expected in an introductory survey.

Supplementary Readings

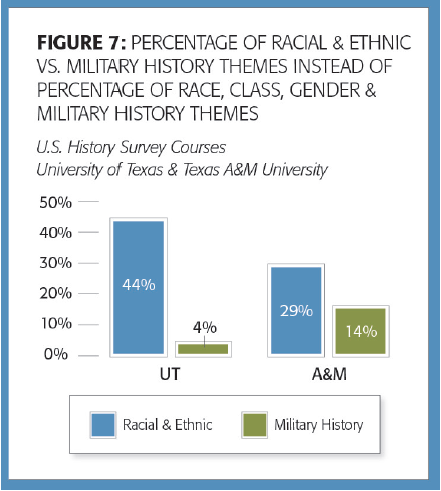

Most survey course instructors (26 of 33 or 79 percent), didn’t use anthologies but collectively assigned 93 supplementary readings from sources they chose individually. These independently assigned readings, with 49 of the 93 assignments (53 percent) having an RCG focus, were much more heavily tilted to race, class, and gender themes than those drawn from anthologies. The differences between UT and A&M were significant. Readings with racial and ethnic themes, for example, comprised 44 percent of the 25 reading assignments at UT, compared to 29 percent of the 66 assignments at A&M. On the other hand, 14 percent of A&M assignments focused on military history, while only 4 percent at UT did.13

Figure 8 provides a list of the 49 of the 93 reading assignments (or 53 percent of the readings not contained in the six anthologies) that were identified as having a focus on race, ethnicity, class, or gender. Taken individually, a case for inclusion in an American history survey, syllabi could certainly be made for most them. Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, are indisputably important texts, and it is unfortunate that the former was assigned by only one faculty member and the latter by only five.14 Several others might also be considered American classics, such as The Shame of the Cities or the film The Grapes of Wrath. But once more the issue is the relative emphasis on RCG content compared to other themes and topics.

| READING | PERSPECTIVE/ANALYTICAL APPROACH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | Gender | Class | ||

| 1 | Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary American Woman | X | ||

| 2 | American Negro Slavery | X | ||

| 3 | American Slavery: 1619-1877 | X | ||

| 4 | Apostles of Disunion | X | ||

| 5 | Becoming America: The Revolution Before 1776 | X | X | |

| 6 | Black Boy | X | ||

| 7 | Black Like Me | X | ||

| 8 | Bonds of Womanhood: Woman’s Sphere in New England, 1780-1835 | X | ||

| 9 | Cesar Chavez and La Causa | X | X | |

| 10 | Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England | X | ||

| 11 | Coming of Age in Mississippi | X | X | |

| 12 | Grapes of Wrath (Movie) | X | ||

| 13 | Great Depression | X | ||

| 14 | Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men | X | ||

| 15 | Harvest Gypsies, On the Road to the Grapes of Wrath | X | ||

| 16 | I Came a Stranger: The Story of a Hull House Girl | X | X | |

| 17 | Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl | X | X | |

| 18 | Jackie Robinson and the American Dilemma | X | ||

| 19 | Landon Carter’s Uneasy Kingdom: Revolution and Rebellion on a Virginia Plantation | X | X | |

| 20 | Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian Democracy | X | ||

| 21 | Masters without Slaves | X | X | |

| 22 | Myne Owne Ground: Race and Freedom on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1640-1676 | X | ||

| 23 | Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass | X | ||

| 24 | Natives and Newcomers: The Colonial Origins of North America | X | ||

| 25 | New England Town: The First Hundred Years | X | ||

| 26 | New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America | X | ||

| 27 | Our Contemporary Ancestors in the Southern Mountains | X | ||

| 28 | Out of This Furnace: A Novel of Immigrant Labor | X | ||

| 29 | Promised Land: The Great Black Migration | X | ||

| 30 | Propaganda of History, From Black Reconstruction (1935) | X | X | |

| 31 | Race and Revolution | X | ||

| 32 | Ragtime | X | X | |

| 33 | Reconstruction | X | X | |

| 34 | Red, White, and Black | X | X | |

| 35 | Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft | X | ||

| 36 | The Scratch of a Pen | X | ||

| 37 | The Shame of the Cities | X | ||

| 38 | Shay’s Rebellion | X | ||

| 39 | Sitting Bull and the Paradox of Lakota Nationhood | X | ||

| 40 | Social Reform—Jacksonian Era: Beauty, the Beast, and the Militant Woman | X | ||

| 41 | Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market | X | ||

| 42 | The Good Old Days: They Were Terrible! | X | ||

| 43 | The Minutemen and Their World | X | X | X |

| 44 | The Shoemaker and the Tea Party | X | ||

| 45 | The South versus the South | X | ||

| 46 | Uncle Tom’s Cabin | X | ||

| 47 | Warriors Don’t Cry | X | ||

| 48 | Women at Work | X | ||

| 49 | Women’s Rights Emerges with the Antislavery Movement | X | ||

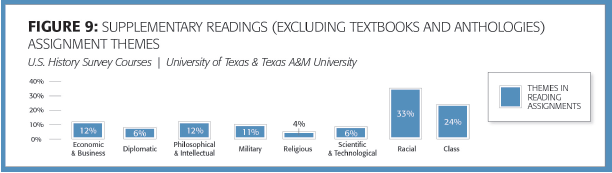

Among readings (excluding textbooks and anthologies) assigned individually by history faculty members in what were supposed to be general survey courses in American history, only 12 percent dealt with economic and business history, 6 percent with diplomatic and international affairs, 12 percent with philosophical and intellectual history, 11 percent with military history (only 4 percent at UT-Austin), 4 percent with religious history, and 6 percent with scientific and technological history, compared with 33 percent with racial themes, 24 percent with social class themes, and 11 percent with gender themes.15

Commercial Anthologies in Survey Courses

Seven faculty members assigned materials (i.e., articles, extracts, and documents) drawn from six different commercial anthologies, containing in total 332 separate reading assignments.16One anthology, Reading the American Past, was assigned by two faculty members at UT; all others were assigned in only one course. The number of articles assigned from each anthology varied significantly. While one anthology, For the Record II, had 144 assigned readings, two, After the Fact and Going to the Source, had only 11 assigned readings apiece. Moreover, except for the two faculty members at the University of Texas who assigned the same anthology, there was limited overlap in the articles read by students, only six articles out of the 332 appearing in more than one anthology.

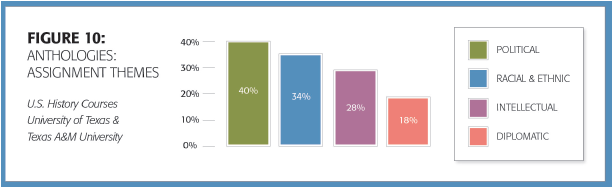

Forty-five percent of the readings assigned from the anthologies were categorized as RCG, and the RCG content of the 332 articles ranged from a low of 36 percent in one anthology to a high of 55 percent in another.17 Among these, political themes were most frequent at 40 percent, followed by racial and ethnic themes at 34 percent. But intellectual and diplomatic topics were also fairly well represented at 28 percent and 18 percent, respectively.<18

Primary Source Documents in Survey Courses

Many political documents that one would expect to find in an American history survey were missing from the reading assignments. Classic historical memoirs or autobiographies were rarely assigned.

The six assigned anthologies were not helpful in providing access to primary source documents. Only one anthology assigned by only two faculty members (Reading the American Past) gave students reading assignments that included George Washington’s Farewell Address, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Gettysburg Address. Only one faculty member assigned the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Of the 33 faculty members who taught survey courses, only four assigned even portions of the Notes on the State of Virginia by Thomas Jefferson and only one assigned Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville. The most assigned primary political text, assigned by seven faculty members, was Common Sense by Thomas Paine. The U.S. Supreme Court decision, Dred Scott v. Sanford, was assigned by only two faculty members. Only one instructor provided access to other key Supreme Court decisions, including Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. the Board of Education. Classic political documents such as the Mayflower Compact and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address were not assigned by any faculty members.

Other than the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass with five assigners and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs with four, there were no historically important memoirs or autobiographies included in the assignments. Missing from the assignments were any selections from autobiographies by Ulysses S. Grant, Booker T. Washington, or Harry S. Truman. Moreover, rarely did reading assignments contain anything about figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Dewey, Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas A. Edison, the Wright brothers, or the scientists of the Manhattan Project.

Some faculty members assigned novels. Three at Texas A&M assigned Killer Angels: A Novel of the Civil War by Michael Shaara. Individual instructors at A&M also assigned All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane, and Ragtime by E.L. Doctorow. At UT, one faculty member assigned a novel about immigrants, Out of this Furnace: A Novel of Immigrant Labor by Thomas Bell, and one assigned Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

In determining the texts U.S. history courses were missing, we sought a standard list of the most important ones. We consulted the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), which has published a list of 100 “milestone documents” of U.S. history from 1776 to 1965.19 NARA reports that it chose these 100 because “they have helped shape the national character, and they reflect our diversity, our unity, and our commitment as a nation to continue our work toward forming ‘a more perfect union.’”20

We compared the UT and A&M U.S. history assigned readings with this list because it was compiled by an independent organization and provides a good representation of some of the most important primary sources in U.S. history.212223

Of these 100, only 23 were assigned, and these were assigned by only five faculty members (out of the 46 total), two at A&M and three at UT. In other words, 89 percent of faculty members teaching lower-division U.S. history courses assigned none of the 100 key documents, and 77% of the documents went totally unassigned. The 23 assigned documents were:

• Declaration of Independence (1776)

• Articles of Confederation (1777)

• Constitution of the United States (1787)

• Federalist Paper No. 10 and No. 45 (1787)

• Bill of Rights: 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments (1865, 1868, 1970)

• President George Washington’s Farewell Address (1796)

• Alien and Sedition Acts (1798)

• Marbury v. Madison (1803)

• Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857)

• Emancipation Proclamation (1863)

• Gettysburg Address (1863)

• Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)

• Dawes Act (1887)

• Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

• Theodore Roosevelt’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (1905)

• Zimmerman Telegram (1917)

• Joint Address to Congress Leading to a Declaration of War Against Germany (1917)

• Franklin D. Roosevelt: “The Four Freedoms” (1941)

• Truman Doctrine (1947)

• Marshall Plan (1948)

• Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

• President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Farewell Address (1961)

• President John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address (1961)

Most students taking U.S. history courses, however, did not have exposure to any of these key works of American history.24

Eleven course syllabi noted that additional readings would be available in separate handouts, on the course website, in the online library system, on Blackboard, or on JSTOR. Because they were not listed on the publicly available syllabi, we did not have access to the titles of these readings.

The available information on the syllabi, however—showing an absence of most key primary source documents—verifies that the domination of RCG themes results in cuts to important readings.

Textbooks in Survey Courses

Twenty-nine of the 33 faculty members teaching survey courses assigned 17 textbooks. Four faculty members did not use a textbook while three assigned two textbooks in each of their courses. Only nine texts, shown on Figure 12, were adopted by two or more faculty members, while another eight were adopted by only one faculty member.

We classified the 17 textbooks into the three categories of RCG focus: high, moderate, and limited. Seven had high emphasis on race, class, and gender; two had moderate RCG emphasis; and eight had limited RCG emphasis, as shown in Figure 12. There was a sharp contrast between UT and A&M in the thematic tilt of the textbooks adopted. Of the 24 textbook assignments at Texas A&M, 12 (50 percent) assigned textbooks with limited RCG emphasis, two (9 percent) counteracted a high RCG text with a limited RCG one, and seven (29 percent) assigned only a high RCG text. On the other hand, of the nine textbook-using faculty members at UT, only two (25 percent) assigned a text with limited RCG emphasis, one (13 percent) counteracted a high RCG with a limited RCG text, and seven (88 percent) assigned a high RCG text (see Table 5 in Appendix 1 for numbers of textbook assignments in each RCG level).

| Multiple Assigners* | ||||

| Title | RATING | LEAD AUTHOR | # OF ASSIGNERS | INSTITUTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| America, A Narrative History, Vol I & Vol II | Limited | Tindall, George | 5 | A&M |

| America: A Concise History, Vol I & Vol II | Moderate | Henretta, James | 4 | A&M |

| Give Me Liberty! An American History, Vol I | High | Foner, Eric | 3 | A&M (1) UT (2) |

| A People’s History of the United States | High | Zinn, Howard** | 3 | A&M (2) UT (1) |

| Unfinished Nation, Vol I and Vol II | Limited | Brinkley, Alan | 2 | A&M |

| Nation of Nations, Vol I | High | Davidson, James | 2 | UT |

| US: A Narrative History, Vol 2 | High | Davidson, James | 2 | UT |

| Visions of America | High | Keene, Jennifer | 2 | A&M |

| A History of the American People | Limited | Johnson, Paul** | 2 | A&M (1) UT (1) |

| One Assigner | ||||

| America: Past and Present | Limited | Robert Devine | 1 | A&M |

| The American Past | Limited | Joseph Conlin | 1 | A&M |

| The American People | High | Gary Nash | 1 | A&M |

| American Stories | Limited | H. W. Brands | 1 | UT |

| A History of the American People | Limited | Stephen Thernstrom | 1 | A&M |

| Of the People | High | James Oakes | 1 | A&M |

| Out of Many | Moderate | John Faragher | 1 | A&M |

| A Patriot’s History of the United States | Limited | Larry Schweikart | 1 | A&M |

* Textbook assigned by more than one faculty member

** The Zinn text and the Johnson text were twice paired with another to provide “interpretative balance”—once at A&M and by another at UT. The Zinn text was paired once with the Schweikart text at A&M.

Texas History Courses

At A&M, three out of the five faculty members teaching Texas history courses (60 percent) were classified as high assigners of RCG readings, while both UT faculty members (100 percent) were high assigners of RCG readings.

Eight sections of Texas history, taught by seven faculty members, were offered at the two institutions. The six taught at A&M were lower division courses fulfilling the American history requirement. These sections were taught by five faculty members, with one visiting professor offering two sections. At the University of Texas two faculty members taught one section of Texas history each, and these two sections were upper division classes (although they also qualified as fulfilling the American history requirement).

Six out of the seven Texas history instructors assigned one of three textbooks.25 (The other faculty member did not use a textbook.) Instructors also assigned twenty-one other readings, including four films (see Figure 13). Of the supplementary assignments, 73 percent had a race, class, or gender emphasis,26 substantially more than those in the survey courses.

| RACE, CLASS OR GENDER TOPIC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| READING | YES | NO | ||

| 1 | Black Texans: A History of African Americans | X | ||

| 2 | Border Bandits—The Texas Rangers and the Legacy of Racial Violence (film) | X | ||

| 3 | Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier | X | ||

| 4 | Claiming Rights and Righting Wrongs in Texas, Mexican Workers and Job Politics during WWII | X | ||

| 5 | Creating the New Woman: The Rise of Southern Women’s Progressive Culture in Texas, 1893-1918 | X | ||

| 6 | Farewell: A Memoir of a Texas Childhood | X | ||

| 7 | Feeding the Wolf: John B. Rayner and the Politics of Race, 1850-1918 | X | ||

| 8 | Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery at Beaumont, Texas in 1901 | X | ||

| 9 | Homesteads Ungovernable: Families, Sex, Race, and the Law in Frontier Texas, 1823-1860 | X | ||

| 10 | Life Among the Texas Indians: The WPA Narratives | X | ||

| 11 | Lone Star Stalag, German Prisoners of War at Camp Hearne | X | ||

| 12 | Major Problems in Texas History | X | ||

| 13 | Modern Texas, 1971-2001, in Gone To Texas, A History of the Lone Star State | X | ||

| 14 | Sam Houston and the American Southwest | X | ||

| 15 | Sleuthing the Alamo: Davy Crockett’s Last Stand and Other Mysteries of the Texas Revolution | X | ||

| 16 | Strange Career of Bilingual Education in Texas 1836-1981 | X | ||

| 17 | Tejano Legacy: Rancheros and Settlers in South Texas, 1734-1900 | X | ||

| 18 | The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter (film) | X | ||

| 19 | They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes Toward Mexicans in Texas 1821-1900 | X | ||

| 20 | When I Rise: The Story of Barbara Smith Conrad (film) | X | ||

| 21 | “With His Pistol in His Hand”: A Border Ballad and Its Hero | X | ||

Special Topics Courses

Overall, faculty members at UT were typically higher assigners of RCG themed readings than faculty members at A&M. This institutional difference was partly a function of the prevalence of special topics courses with high RCG content at the University of Texas.

Nine sections of special topics courses covered specific topics in American history rather than giving a broad overview. Students can take these courses to satisfy the legal requirement for American history study. The seven topics covered in the semester we studied (also listed on Figure 14) were “History of American Sea Power” (Texas A&M); “History of Mexican Americans in the US”; “Introduction to American Studies”; “Black Power Movement”; “Mexican American Women, 1910-present”; “Race and Revolution”; and “The United States and Africa” (University of Texas).27

As their titles suggest, special topics courses at UT were thematically lopsided. All of the eight faculty members teaching these courses made high usage of race, class, and gender readings—over 50 percent of their reading assignments focused on RCG topics.

While special topics courses were neither U.S. history surveys nor Texas history courses, they fulfilled the state statutory requirement. UT also appears to do more to encourage students to take its special topics courses as a means of satisfying the statutory American history requirement than does Texas A&M. UT placed these special topics courses next to survey courses in its 2010 course schedule; A&M did not.

All the UT faculty members teaching these courses had an RCG research interest, and all the UT faculty members for these courses were high RCG reading assigners. The instructor at A&M, a military historian, made no RCG assignments in his naval history course. No textbooks were assigned in any of these special topics sections; the teachers relied instead upon 31 specific reading assignments. Three were for the A&M course. At UT, 25 out of 28 assignments were RCG-focused, with 23 of them dealing specifically with race and ethnicity. Figure 15 provides information on the titles and topics of those assignments.

Conclusion

At the University of Texas the special topics reading assignments were heavily dominated by RCG themes, as were the Texas history supplemental reading assignments. All the instructors teaching these courses were high RCG assigners. There were also more variety at both institutions among the American history surveys but with more apparent thematic coverage gaps at the University of Texas. Even in survey courses there remained a problem of crowding out political, economic, diplomatic, and military topics.

In addition to their intense preoccupation with RCG issues, special topics courses failed to present students with an overview of American history’s broader sweep. Encouraging students to satisfy part (or all) of the statutory requirement by taking special topics courses, as the University of Texas appears to do, seems inconsistent with the spirit of the 1955 and 1971 statutes meant to ensure that students gain a command of the larger American and Texan narratives.

| READING | RGC TOPIC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RACE | CLASS | GENDER | ||

| 1 | Africanisms in American Culture | X | ||

| 2 | Assata: An Autobiography | X | X | |

| 3 | Barefoot Heart: Stories of a Migrant Child | X | ||

| 4 | Becoming Mexican-American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1940-1945 | X | X | X |

| 5 | Chicana Feminist Thought | X | X | X |

| 6 | Claiming Rights and Righting Wrongs in Texas, Mexican Workers and Job Politics in WWII | X | X | X |

| 7 | Coming of Age in Mississippi | X | X | |

| 8 | Die, Nigger | X | ||

| 9 | From Out of the Shadows | X | X | |

| 10 | Hanging of Thomas Jeremiah | X | X | |

| 11 | Lakota Woman | X | X | |

| 12 | Little X: Growing Up in the Nation of Islam | X | X | |

| 13 | Looking East from Indian Country | X | ||

| 14 | Mexicanos: A History of Mexicans in the United States | X | ||

| 15 | Mistaking Africa: Curiosities and Inventions of the American Mind | X | ||

| 16 | Negroes with Guns | X | ||

| 17 | Raza Si! Guerra No! Chicano Protest and Patriotism in the Vietnam Era | X | X | |

| 18 | Slacks and Calluses: Our Summer in a Bomber Factory | X | ||

| 19 | Texas Occupational Distribution and Relative Concentration of Mexicans | X | ||

| 20 | The Atlantic World 1450-2000 | X | ||

| 21 | The Shawnees and the War for America | X | ||

| 22 | The Two Princes of Calabar | X | ||

| 23 | Voluntary Organizations and the Ethic of Mutuality | X | ||

| 24 | When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in Colonial New Mexico, 1500-1800 | X | X | |

| 25 | Where the Girls Are: Growing up Female with the Mass Media | X | X | |

Part II—Faculty Members’ Research Interests

Overall Level of Research Interests in Race, Class, and Gender

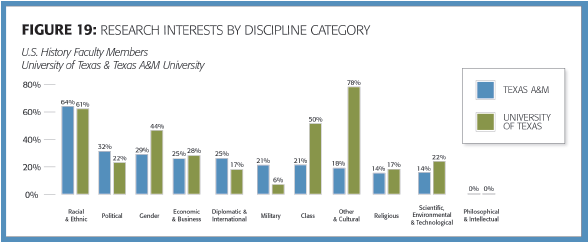

The 46 American history faculty members we studied28 had various areas of specialization, exemplified by the research interests and publications listed on their curricula vitae. This study identifies eleven such areas,29 the same as were used to classify course readings. We placed all 46 faculty members in one or more of the categories that most closely matched the interests expressed in their vitae.30 We derived the following breakdown as summarized on Figure 16.

| DISCIPLINE CATEGORY | Number of Faculty with Interest |

Percentage of Faculty with Interest |

|---|---|---|

| Social History with Racial or Ethnic Emphasis | 29 | 63% |

| Social and Cultural History - Other | 19 | 41% |

| Social History with Gender Emphasis | 16 | 35% |

| Social History with Social Class Relationships | 15 | 33% |

| Political History | 13 | 28% |

| Economic and Business History | 12 | 26% |

| Diplomatic and International History | 10 | 22% |

| Scientific, Environmental, and Technological History | 8 | 17% |

| Military History | 7 | 15% |

| Religious History | 7 | 15% |

| Philosophical and Intellectual History | 0 | 0% |

*Percentages reflect the percentage of faculty members whose expressed research interests fell into one or another of these categories. Because in most cases, faculty members had more than one research interest, the percentage total exceeds 100%. Overall 136 separate research interests were identified and classified into these eleven categories.

The most frequently stated research interest was social history with racial or ethnic emphasis, with 63 percent of all faculty members listing this as an interest.31 Interest in gender and class related subject matter also outranked interest in political history. Not a single faculty member teaching American history expressed a research interest in philosophical and intellectual history.

Figures 17 and 18 contrast faculty members at UT and A&M across all three course categories. This is another one of our central findings: at UT, 78 percent of the faculty members teaching these courses had special research interests in race, class, and gender, and at A&M, 64 percent had RCG research interests.32

For UT faculty members, race/ethnicity, class, or gender were listed in three of the top four research interests. By contrast, at Texas A&M, political history and economic and business history ranked second and fourth, respectively. At A&M, diplomatic and military history also ranked much higher as research interests than they did at the University of Texas. Nonetheless, race/ethnicity still ranked first as an interest at Texas A&M, indicated by 18 of the 28 instructors teaching American history. The most frequently embraced research interest among the University of Texas faculty members teaching American history, as shown on Figure 18, was “Social and Cultural History – Other,” a general category of social history focused on topics such as age, education, and material and visual culture, including performing arts, music, fashion, and architecture. A full definition of this category is provided in Appendix 3.33

Additional categories under social history were “social history with racial or ethnic emphasis,” “social history with gender emphasis,” and “social history with social class emphasis.” At UT 61 percent of the 18 faculty members indicated a more specific interest in race or ethnicity, 50 percent in class, and 44 percent in gender. No other subject attracted the interest of more than 30 percent. At Texas A&M race and ethnicity ranked first at 64 percent, but there was relatively less interest in gender- and class-related topics and more in political, diplomatic, and military subjects. At both institutions, research interest in historical topics related to race and ethnicity, class, and gender showed heavy overlap. In fact, these three research themes were so intertwined that a combined research category of RCG is very appropriate.

| TEXAS A&M (28) | UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS (18) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty with Interest | % of Total Faculty | Faculty with Interest | % of Total Faculty | ||||

| 1 | Social History with Racial or Ethnic Emphasis | 18 | 64% | 1 | Social & Cultural History - Other | 14 | 78% |

| 2 | Political History | 9 | 32% | 2 | Social History with Racial or Ethnic Emphasis | 11 | 61% |

| 3 | Social History with Gender Emphasis | 8 | 29% | 3 | Social History with Social Class Emphasis | 9 | 50% |

| 4 | Economic and Business History | 7 | 25% | 4 | Social History with Gender Emphasis | 8 | 44% |

| 5 | Diplomatic and International Relations History | 7 | 25% | 5 | Economic and Business History | 5 | 28% |

| 6 | Military History | 6 | 21% | 6 | Political History | 4 | 22% |

| 7 | Social History with Social Class Emphasis | 6 | 21% | 7 | Scientific, Environmental, and Technological History | 4 | 22% |

| 8 | Social & Cultural History - Other | 5 | 18% | 8 | Diplomatic & International Relations History | 3 | 17% |

| 9 | Religious History | 4 | 14% | 9 | Religious History | 3 | 17% |

| 10 | Scientific, Environmental, and Technological History | 4 | 14% | 10 | Military History | 1 | 6% |

| 11 | Philosophical and Intellectual History | 0 | 0% | 11 | Philosophical and Intellectual History | 0 | 0% |

Overall, RCG research interests appear to have more favor among American history faculty members at the University of Texas than at Texas A&M.

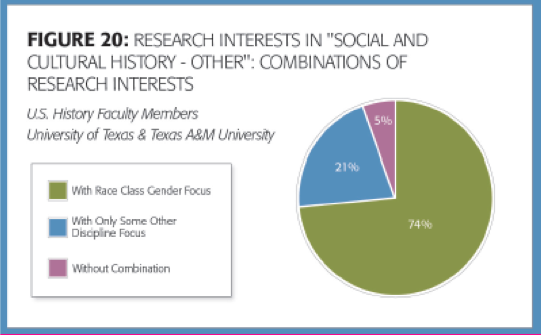

Overlap in Faculty Members’ Research Interests

Most faculty members teaching introductory American history courses had more than one research interest. An analysis of the overlap provides a clearer understanding of how they tended to combine interests. For example, there is a fairly high research interest in “Social and Cultural History - Other,” yet this rarely stood alone, with 74 percent also co-listing a research interest in studies with a minority race/ethnicity, social class, or gender emphasis (see Figure 20 and Table 8 in Appendix 1). This co-listing was less pronounced for Texas A&M faculty members (who had relatively lower levels of interest in the “Social and Cultural History - Other” category overall).

In addition, most faculty members who indicated an interest in race, minority ethnicity, class, or gender, also expressed an interest in another RCG area. Figure 21 below provides details on these connections.34

| Total | A&M | UT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race, Minority Ethnicity with Gender and Social Class |

73% | 67% | 82% |

| Gender with Race, Minority Ethnicity, and Social Class |

88% | 88% | 88% |

| Social Class with Race, Minority Ethnicity, and Gender |

80% | 67% | 89% |

The high frequency of interconnections of race/ethnicity, class, and gender interests suggests that these three categories form a virtually unified sub-discipline that we have been abbreviating as RCG. Figure 21 summarizes the overlap in research interests within the RCG categories. Thus at UT 73 percent of the faculty members with a research interest in race and minority ethnicity were also interested in class and gender-related subjects. Of those interested in social class, 80 percent were also interested in race, minority ethnicity, and gender. Of those with an interest in gender, 88 percent were also interested in race, minority ethnicity, and social class.

Figure 22 provides examples to illustrate the publications and research interest of faculty members with these overlapping interests.

| EXAMPLE #1 | |

|---|---|

| Presentations: | “Finding Common Cause through Race: The Importance of Whiteness to Ethnic Mexican Civil Rights Efforts” |

| “Two Races Fit All: Texas Juries, Race and Mexican American Place” | |

| EXAMPLE #2 | |

| Books: | Becoming African in America: Race and Nation in the English Black Atlantic |

| E Pluribus Unum: Race Formation in the Era of the American Revolution | |

| EXAMPLE #3 | |

| Book: | Black Rage in New Orleans: Police Brutality and African American Activism from WWII to Hurricane Katrina |

| Courses Taught: | Race, Sport and Hip-Hop |

| Race in the Age of Obama | |

| Black Nationalism | |

| Introduction to African American Studies | |

| EXAMPLE #4 | |

| Publication: | “Racism and God-Talk: A Latina Perspective” |

| Presentations: | “Blues to Hip-Hop: Rethinking Black Women’s Sexuality” |

| “Beyond La Chicana: Building the Chicana/o Studies Curriculum” | |

| EXAMPLE #5 | |

| Publication: | “Representing Gender and Race at Railroad Circuses in Victorian America” |

| Courses Taught: | Race, Gender, and American Popular Culture |

| Creating the Female Body in American Popular Culture | |

| EXAMPLE #6 | |

| Publication: | “The First Thing Every Negro Girl Does: Black Beauty Culture, Racial Politics and the Construction of Modern Black Womanhood 1905-1925” |

| Presentation: | “Collecting and Researching Women’s and Gender Issues” |

| EXAMPLE #7 | |

| Dissertation: | “Race, Communicable Disease and Community Formation on the Texas-Mexico Border” |

| Presentation: | “Framing America’s Hard Edges: Photographs, Health Imagery and the (De)Construction of Racialized Belonging” |

| EXAMPLE #8 | |

| Presentation: | “150 Years of Women’s Rights Activism” |

| Course Taught: | “Gender and Social Construction of Illness” |

Race, Class, and Gender Research Interests by Course Type

Thirty-two of the 46 faculty members, or 70 percent, had a research interest in minority ethnicity, social class, or gender.

Significantly more UT than Texas A&M faculty members had a research interest in RCG—78 percent versus 64 percent.35 The eight UT faculty members teaching the special topics courses with an RCG interest constituted most of the difference and were only partially offset by five at A&M teaching Texas history. All five Texas A&M faculty members who taught Texas history had an RCG interest, as did one of the two at UT. When only the faculty members teaching U.S. history surveys were examined, the figure was approximately the same, roughly 61 percent.36

Recent Ph.D.s vs. Earlier Ph.D.s: Research Interests

Differences in research interest correspond significantly with the decade in which faculty members received their doctorates. Thirty-nine of the 46 faculty members we studied had earned a doctorate. Those whose doctorates date from the 1990s or 2000s had a greater likelihood of having an RCG research interest than those who had received them in earlier decades. Of the 39 faculty members at UT and A&M with Ph.D.s, 86 percent (19 out of 22) of those who received their Ph.D.s in the 90s or later had race, class, and gender related research interests. Only 47 percent of those who received their Ph.D.s in the 70s and 80s (8 out of 17) had race, class, and gender-related research interests. Overall 27 of the 39 faculty members (69 percent) with Ph.D.s had RCG interests, and they were more prevalent at UT than at Texas A&M.37 The cohort differences were much greater at Texas A&M than at UT.

At A&M, only 36 percent of A&M faculty members who received their Ph.D.s in the 70s or 80s had RCG research interests, but 90 percent of A&M faculty members who received their Ph.D.s in the 90s or later had RCG research interests. Likewise, only 67 percent of UT faculty members who received their Ph.D.s in the 70s or 80s had RCG research interests, but 83 percent of UT faculty members who received their Ph.D.s in the 90s or later had RCG research interests. This is one of our central findings.

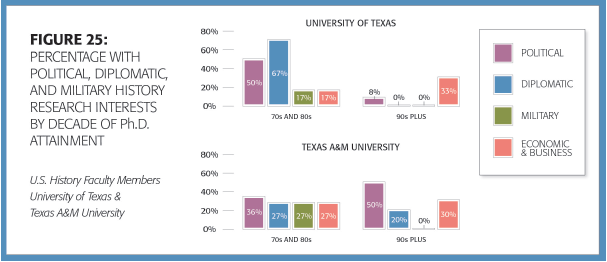

This shift did not come about without severe costs to other sub-fields. For example, 50 percent of UT faculty members with earlier Ph.D.s were interested in political history; in the 90s and later cohort, only 8 percent had such an interest. No UT faculty members in the 90s and later cohort had research interests in diplomatic or military history, although 67 and 17 percent (respectively) of the 70s and 80s cohort were interested in these fields. Even at A&M, despite its long tradition of ROTC participation, interest in military history, which was 27 percent for the 70s and 80s cohort, was zero for the 90s and later cohort. At A&M, however, for faculty members who received their Ph.D.s in later decades, interest in political history was 50 percent, an increase from 36 percent for those with Ph.D.s in earlier decades.38 Among recent doctorates, there has also been a greater interest at A&M in diplomatic and international history.39 On the other hand, at both institutions recent doctorates had comparable research interest in economics or business.4041

Conclusion

As demonstrated by their CVs and self-descriptions on department websites, the research professors engage in focuses heavily on group identities, a situation more pronounced at UT than at Texas A&M. While a greater proportion of the junior faculty members at A&M teaching these courses have RCG interests, they also show more interest in political and diplomatic history than do their peers at UT. Moreover, the RCG percentages at A&M were influenced by the prominence of recent Ph.D.s as adjuncts who had RCG interests.

Part III—Associations Between Reading Assignments and Research Interests

Overall Extent of Race, Class, and Gender Themes in Reading Assignments

We found that of those who taught American history survey courses and had RCG interests (at both universities), 55 percent were high assigners of RCG readings (see Table 14 in Appendix 1).

At Texas A&M, of the nine faculty members who did not have an RCG research focus, 44 percent (four) were high assigners of RCG readings, while among the 14 RCG research-focused faculty members, 57 percent (eight) were high assigners. On the other hand, this direct relationship did not hold at UT; both RCG and non-RCG faculty were predominately high assigners of RCG readings, and non-RCG faculty members were actually higher assigners of RCG readings than were RCG research-focused faculty members.

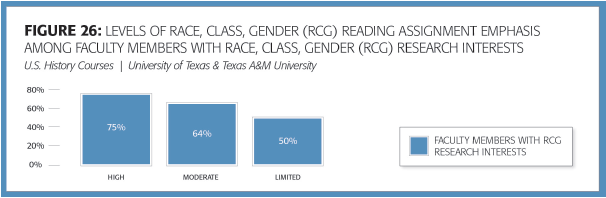

The figure below shows the association between research interest and reading assignments for all 46 faculty members for all course types. The data show that high assigners of RCG readings were very likely to have an RCG research interest. For example, among faculty members with RCG research interests, 75 percent were high assigners of RCG readings.42 Faculty members with RCG research interests were more likely to be high assigners than moderate or low assigners of RCG reading assignments. At UT the association was particularly strong as a result of RCG faculty members teaching heavily RCG-dominated special topics courses.

Recent Ph.D.s vs. Earlier Ph.D.s

At UT the tendency to assign RCG readings is somewhat greater among those faculty members who received their doctorates more recently. This suggests that the preponderance of RCG topics at UT will likely increase over time. With respect to hires, as an institution sows (new faculty hires with strong RCG research interests), so shall it likely reap (greater one-sidedness of reading assignments).

At A&M, however, only 30 percent of those who earned their Ph.D.s later assigned high RCG readings, whereas of those who earned Ph.D.s in the 70s and 80s, 46 percent assigned high RCG readings.

| Ph.D.s 70s and 80s RCG High Use % |

Ph.D.s 90s and Beyond RCG High Use % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Both (39) | 53% (17) | 59% (22) |

| A&M (21) | 46% (11) | 30% (10) |

| UT (18) | 67% (6) | 83% (12) |

*Numbers in parentheses represent faculty member counts in each category.

Note on History Department Faculty Members

We note that our analysis did not cover entire history departments but only a subset of 46 faculty members: those teaching (in the Fall 2010 semester) lower-division American history courses that satisfied the state’s legislative requirement. For that semester, UT listed 94 faculty members in its history department (including both senior and visiting lecturers). There were 40 professors of U.S. history, 18 of whom were in the cohort for this study. Although fewer than half of the U.S. history faculty members at UT are examined here, the 18 we looked at are worth considering separately because they are the ones teaching the courses that satisfy the legislative requirement for U.S. history.

At A&M that semester, 59 faculty members were listed, including visiting and joint appointment faculty members. In addition, nine adjunct faculty members were listed. Of the 28 A&M faculty members in our study, 16 were faculty members, three were visiting and associate faculty members, and nine were adjuncts.

The adjuncts played a significant role in the level of RCG research interests among the cohort of A&M teachers in this study. Seven of the nine had RCG research interests. This means that, at least at A&M, RCG research interest may not necessarily be self-reproducing unless adjuncts are the ones teaching these courses consistently from year to year. Ultimately, however, what matters most is the students’ experience, which is essentially the same whether the RCG-focused teacher is a full professor or an adjunct lecturer.

Survey Courses

There was very little connection between high assignment of RCG readings and RCG research interest when we look only at American history survey courses combined for both UT and A&M. These were the courses students fulfilling the American history requirement were most likely to take, taught by 23 faculty members at A&M and 10 at UT. As Table 12 (with textbook assignments included) and Table 13 (with only supplemental readings) in Appendix 1 show, among these survey courses faculty members with RCG research interests were about as likely to be moderate and limited assigners of RCG reading materials as they were to be high assigners.

This combined data, however, masks significant institutional differences, with non-RCG A&M faculty members far less likely to be high assigners than the RCG faculty members at A&M or the non-RCG faculty members at UT (see Tables 14 and 15 in Appendix 1). Thus at A&M, there is a clear association between RCG research interests and the likelihood of being a high assigner of RCG readings, while this is not the case at the University of Texas. One possible reason for this is the difference in institutional climate between the two institutions; the climate at UT appears to encourage all faculty members to assign RCG readings no matter what their research interests are.

Anthologies

As shown on Figure 28, there was not a clear association between research interest and patterns of assigning anthologies, perhaps because very few faculty members used anthologies and only two of the seven faculty members using anthologies had an RCG research focus.43

| Anthology | Assigners | Faculty Focus RCG? |

Total Readings | RCG Assigned Readings | % RCG Assigned Readings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After the Fact | 1 | N | UT | 11 | 6 | 55% |

| America Compared | 1 | N | A&M | 22 | 9 | 41% |

| For the Record I | 1 | Y | A&M | 66 | 31 | 47% |

| For the Record II | 1 | Y | UT | 144 | 63 | 44% |

| Going to the Source | 1 | N | A&M | 11 | 4 | 36% |

| Reading the American Past | 2 | N | UT | 78 | 38 | 49% |

| 7 | 2 of 7 | 332 | 151 | 45% |

Textbooks and Supplemental Readings

Eleven of the 29 textbook-assigning faculty members (38 percent) assigned one high RCG textbook by itself (see Figure 29 below). Three others (10 percent) paired Howard Zinn’s textbook A People’s History of the United States—a high RCG text—with a limited RCG text, either Paul Johnson’s A History of the American People or Larry Schweikert’s A Patriot’s History of the United States. There was no substantial relationship between the thematic content of the textbook chosen and faculty research interest, and to the small extent to which there was one it was inverse. Of the 11 who did not have RCG research interests, six (55 percent) assigned RCG focused textbooks. It was the institution at which the instructor taught, not personal research interest, which appeared to have the most to do with the type of text chosen.

The assignments by Texas A&M faculty members show that those with an RCG research interest made greater use of RCG textbooks and RCG supplemental readings, and that those without such interests made greater use of non-RCG textbooks and non-RCG supplemental readings. In contrast we found that at UT-Austin, both RCG research-interested faculty members and non-RCG research-interested faculty members assigned RCG textbooks at a high rate, no UT faculty member without an RCG interest used a non-RCG text, and two out of four in this group were also high assigners of RCG supplemental readings. The results at UT show again that the institutional climate at UT encourages the use of RCG materials, whether or not the faculty members have such interests.

| RGC Faculty | Non-RGC Faculty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Textbook Classification | Total # | # | % | # | % |

| High RCG textbook alone | 11 | 5 | 28% | 6 | 55% |

| Moderate RCG textbook | 5 | 3 | 16.7% | 2 | 18% |

| Limited RCG textbook | 10 | 7 | 39% | 3 | 27% |

| High RCG textbook paired with Limited RCG textbook | 3 | 3 | 16.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Totals | 29 | 18 | 100% | 11 | 100% |

Texas History Courses

Six out of the seven faculty members teaching the history of Texas had an RCG research interest and this seems to have had some influence on assignments;44 Professors teaching Texas history made heavy use of RCG readings. Only one of the two UT faculty members had an RCG research interest, but both were high assigners of RCG materials, whether or not their textbook reading assignments were considered. At Texas A&M, all five faculty members had an RCG research interest, but fewer were classified as high RCG assigners if textbook assignments were included. That is, three of the five RCG faculty members were high assigners of RCG readings while two were moderate assigners if textbooks were included, but all five were considered high assigners if we look exclusively at the supplemental reading assignments (see Tables 16 and 17 of Appendix 1).

Special Topics Courses

Particularly in special topics courses, faculty members appeared to be organizing and designing courses around their own research interests. Perhaps they chose to teach special topics courses because of that opportunity. Indeed, every UT special topic course reflected the RCG interests of the faculty member teaching it and all these faculty members were high assigners of RCG reading assignments.

Part IV—Implications

Our findings in this study shed light on a source of Americans’ increasing ignorance about their own history. At the two institutions we studied, the focus on race, class, and gender often tended to crowd out the teaching of other perspectives, and many U.S. history courses failed to provide a comprehensive rendering of U.S. history as a whole. Thematically skewed teaching leads to an incompleteness of knowledge, as recent studies of American history knowledge among students demonstrate.45